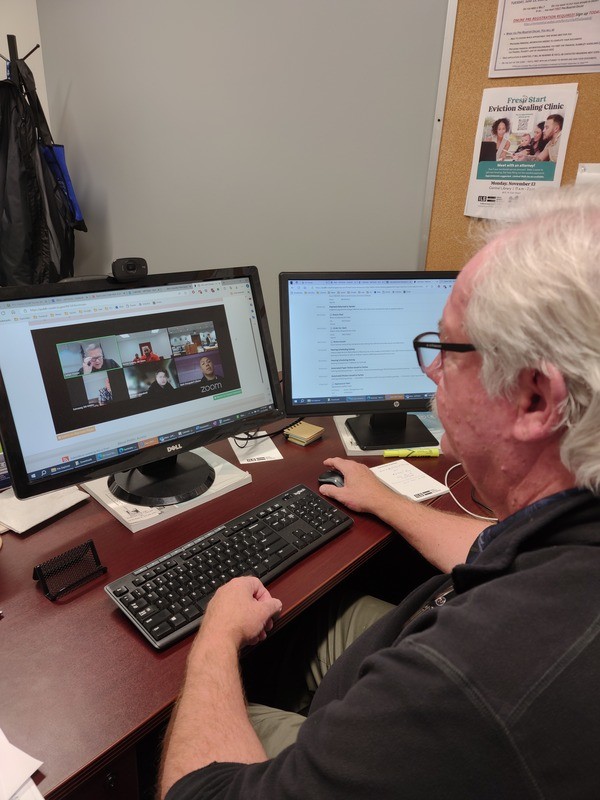

Jeff Heck, director of the pro bono project for Indiana Legal Services, demonstrates remote access to a court hearing from his desktop computer. (Photo/Marilyn Odendahl)

The Indiana Citizen

December 22, 2023

When presiding over a hearing, Monroe County Circuit Court Judge Catherine Stafford keeps in mind the lessons she learned as a waitress serving hungry, angry customers.

The same tenets of customer service used to diffuse and calm a difficult table of guests work well with litigants who enter a courtroom in a “fight, flight or freeze” response mode. Stafford’s docket of family law, small claims, evictions and orders of protection can induce a flow of emotions as plaintiffs and defendants worry they will not be able to see their children, struggle to keep from becoming homeless and wonder how they will pay the thousands of dollars to fix a neighbor’s fence.

Her biggest job when hearing a case, Stafford said, “is to treat it with the formality that I should but also be calm and friendly, or at least, warm and respectful to people, so that I can help calm them to the point that they can make good decisions for themselves and think through what they want to tell me about their case.”

Applying good customer service does more than keep order in the court. If the litigants can remain cool and composed, Stafford said, then they will be able to tell her their side of the story. Then she will be able to make the best decision because she will have all the facts.

A study led by Victor Quintanilla, professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law in Bloomington, shows that technology also can provide some of that same level of customer service to the courtroom experience. Specifically, Quintanilla and his team discovered that litigants were less stressed and more satisfied with the outcome when they attended a court hearing remotely, rather than in person.

The report, “Accessing Justice with Zoom: Experiences and Outcomes in Online Civil Courts,” examined people’s courtroom experiences with digital hearings since the pandemic’s arrival increased their use. During 2020, Indiana courts, like many across the country, shifted most of its proceedings to a virtual format to keep people safe from the COVID-19 virus. Now that everyone is back in person, the courts are deciding if remote hearings should continue in the post-pandemic era.

Quintanilla focused the study on Indiana, collecting data from civil court hearings conducted around the state during 2022. The study surveyed litigants in civil cases, including eviction, debt collection, and family law like child support and divorce, where more than 2,030 of the roughly 2,400 respondents did not have an attorney representing them in court.

At the start of the research, Quintanilla hypothesized that litigants would prefer to appear in person at a hearing rather than attend via Zoom. He was surprised when the data showed the opposite.

The study concluded that the respondents to the survey “spoke loudly and resoundingly: online civil courts enhance access to justice for unrepresented litigants.”

Quintanilla does not foresee the preference for virtual hearings diminishing over time.

“My sense is that probably increasingly, ordinary citizens are going to want to have the remote option, whether that’s phone calls or online, when it comes to having to show up to things that are short in time and difficult to get to,” Quintanilla said. “It’s just going to be something that’s kind of demanded now that it’s available.”

Giving everyone equal footing

The popularity of Zoom hearings is linked to the stress of appearing in person in a courtroom, Quintanilla said. Even as the courts work on being more open and accessible, people arrive anxious and fearful because they do not know what to do or what is going to happen.

Being able to appear while seated at their kitchen table or on their couch helps to reduce the stress, especially for the unrepresented defendants, Quintanilla said. Remote access offers comfort and convenience, because the litigants do not have to upend their day to get to the courthouse.

“It’s helpful to think about this from the perspective of someone who’s working two jobs, caring for kids, trying to make ends meet, already juggling intense demands just trying to stay above water,” Quintanilla said. “Just the sheer outlay of time and energy and burden to have to arrange to go in person in comparison to the remote option, which provides all the conveniences of not having to arrange child care, not having to travel and being able to dial in or remote in from your home or your workplace, it just became a superior option for these individuals.”

The convenience factor could broaden the impact of remote hearings by helping to address the problem of unrepresented, also known as pro se, litigants. Stafford said the number of people coming to court without attorneys has been rising for years and is putting a heavy burden on the docket. Generally, these individuals slow the judicial process because they do not know the proper form to file or understand the rules of the court, which, in the end, can make them more vulnerable to a bad outcome.

Legal aid attorneys are available to represent low-income litigants in civil cases, but the need has become overwhelming.

Jon Laramore, executive director of Indiana Legal Services, a statewide legal aid provider, believes remote hearings could enable his attorneys to serve more clients. Zoom access eliminates the need to travel, so the hours the lawyers would spend driving to and from court, especially in rural communities, could be used to meet, advise and represent indigent individuals needing legal assistance.

Still Laramore cautioned remote access is only part of the answer. Attorneys would have to have adequate contact with the client both before and during the hearing, and would likely have to make the trip to appear in person to avoid being put at a disadvantage if the opposing party is physically present.

“Lawyers just want to make sure that everybody’s on an equal footing,” Laramore said.

Stafford levels the playing field in her court by holding in-person hearings where the parties are introducing evidence and presenting testimony. She has presided over multiple-day contested hearings virtually, but she said it works best when both litigants are represented by attorneys and all the parties can access the proceeding with either a laptop or desktop computer.

When everyone is in person during a contested hearing, Stafford said she can better read the room, knowing when to call for a brief recess, and the individuals can clearly see and hear all that is happening, which can be difficult when people are Zooming over their smartphones. Also, she said, the parties take the proceeding more seriously when they are physically in the courtroom.

“With Zoom, too many people get a little bit too relaxed,” Stafford said. “I have seen some things and (had to ask), ‘Could you put the bong away before you get to court?’ I literally had to make a Post-it note at one point that said, ‘Please wear a shirt during court. Thank you.’”

Few glitches, happier outcomes

Other keys findings from the study include connectivity and satisfaction.

Although Quintanilla said he and his team had expected to see remote hearings stumble over the digital divide, they found the problem was smaller than anticipated. They learned that technological hurdles, like not having access to high-speed internet, occurred in less than 10% of the cases, but those also were the cases where litigants faced the steepest challenges getting to an in-person hearing.

“Knowing that this vulnerable group could have technological hardships and difficulties, we really need to be thinking about ways of supporting them in these remote hearings,” Quintanilla said, “and making sure that we make this option available, because they would have immense difficulty getting to court in person and may not show up at all.”

The study also measured how the litigants felt at the end of their cases. It found little change in the results of a case when comparing in-person and virtual hearings. Unrepresented plaintiffs said they won 85% and 88% of the time in in-person and remote hearings, respectively, while unrepresented defendants said they won 58% and 59% of the time.

What did change, however, was their perception of the outcome. In particular, the defendants were more satisfied with the result of remote hearings.

“I think that’s because it didn’t come with any of the other burdens,” Quintanilla said. “In other words, if you get the same outcome but you don’t have to have as many hurdles to get there, I think you’re more satisfied with that ultimate outcome.”

Andrew Thomas, housing resource attorney for Indiana Legal Services, understands the barriers that low-income litigants can have just getting to the courthouse. And once they are in the building, they can have trouble finding the right courtroom.

Thomas said he prefers his clients to attend in person for most hearings, especially when there is a possibility of an issue being argued. But he has seen clients who have young children or are disabled or do not have reliable transportation struggle to make the appearance.

While remote access can help lower those barriers, Thomas pointed out that simple kindness, such as offering a piece of candy or saying, “good morning,” can reduce the stress many litigants feel. Another way to lessen the tension is having representation.

“Just a little bit of empathy goes a long way,” Thomas said. “I’ll say to people, often, ‘Hey, one of the reasons we as attorneys are here is because we’re used to the stress. We’ve done these kinds of cases more than once.’ So we take on that stress for you. If you don’t have that buffer, you’re going to be in crisis mode while also trying to present your case.”

Dwight Adams, a freelance editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.