By Marilyn Odendahl

The Indiana Citizen

February 12, 2026

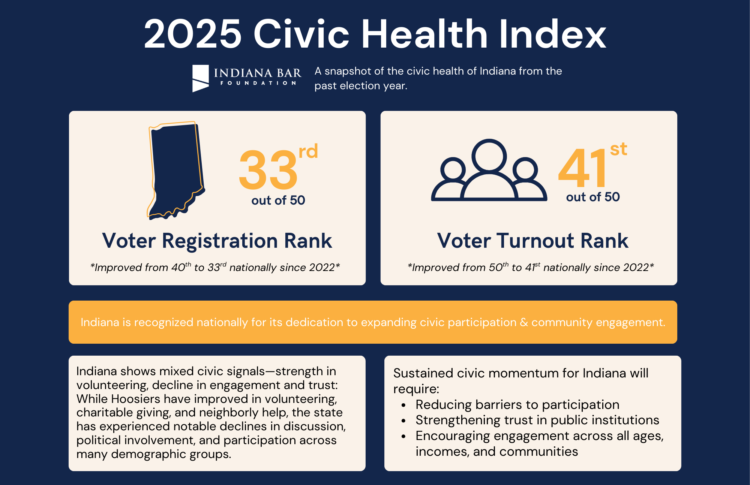

The 2025 Indiana Civic Health Index shows Hoosiers not only are continuing to struggle to get to the voting booth but also may be losing some of their neighborly disposition.

Led by the Indiana Bar Foundation, a team of academics from across the state, working in collaboration with the National Conference on Citizenship, measured the state’s civic health. They examined Hoosiers’ participation in elections and community activities and they assessed the potential for Indiana’s growing commitment to civic education.

The bar foundation and its partners have published a civic health index about every two years since 2011. Each report measures key issues of civic life in Indiana and offers recommendations for getting more Hoosiers to participate in their communities.

A persistent drag on the state’s civic health is voting. For the 2022 midterm election, just 41.9% of Hoosiers eligible to vote actually cast a ballot and Indiana sank to 50th nationally for voter turnout. Two years later, 60% of registered voters in Indiana voted in the 2024 presidential election but still the state climbed to just 41st in the country.

Meanwhile, civic engagement, the fuel for voting, was a mixed bag. Indiana’s national rankings for volunteering, doing favors for neighbors and charitable giving climbed noticeably, but the rankings for social interactions, such as discussing issues with family, neighbors and friends, and political involvement, including following politics and attending a public meeting, have nosedived.

Civic health ripples beyond the voting booth, according to the 2025 Civic Health Index. It underpins a vibrant democracy as well as improves public policies and the effectiveness of government. Moreover, civic health can boost economic, physical and psychological wellbeing of Hoosiers.

“Civic health is strengthened when common ground is found,” the 2025 index said. “When citizens are actively engaged and are supported, they can identify common goals and use their shared knowledge to solve problems in all areas of community concern.”

The data from Indiana’s 2024 election shows the voting process seems to be the stumbling block to the ballot box. Two years ago during the presidential contest, 73.7% of eligible Hoosiers were registered to vote, about equal to the national registration rate, but just 60.7% actually voted, which is below the national voting rate.

Much of the voter turnout in 2024 was carried by Hoosiers age 30 and over with 64.0% of that demographic casting a ballot compared to 46.4% of registered voters age 18 to 29.

David Roof, director of the Center for Economic and Civic Learning at Ball State University, analyzed the voting data in the 2025 index. He found young voters were confused by the registration process. They were not sure where to register to vote, what identification they had to have, how to update their addresses after a move, and whether they could vote by absentee ballot.

Ironically some of the so-called safeguards put in place in the state to build voter confidence in elections have created more skepticism of the system. For example, while some groups said they were reassured by the voter ID requirement, others, especially students, renters and infrequent voters, perceived it as a barrier that signals election officials’ distrust of ordinary citizens.

More voter-friendly policies that have been adopted by other states might help, Roof wrote. Longer polling hours, accessible vote centers and streamlined registration, along with same-day registration, automatic voter registration and no-excuse absentee voting, could also help more people vote in elections.

The 2025 index cited to surveys that show young voters want to participate in elections and they have strong intentions to vote, but, often, they are discouraged, feeling their votes would not make a difference. Some said when they vote they are often choosing between candidates they do not want or that politics was “too much effort for too little impact.” Others emphasized that having better candidates and more transparent processes would motivate them to get to the ballot box.

Combating the common refrain, “my vote doesn’t matter,” requires civic education in schools that helps Hoosiers learn how to be informed voters, Roof wrote. Also beneficial are local news outlets, community forums and “clear, nonpartisan guidance” about the voting process.

“These resources help Hoosiers cut through misinformation and connect their individual voices to collective outcomes,” Roof wrote in the 2025 index. “Where social capital is higher, residents report more confidence in institutions and greater willingness to participate; where it is thin, misinformation and apathy spread more easily.”

Social connectedness and political involvement are declining in Indiana with no clear cause and no indication of whether they are part of a long-term trend. However, a continued slump could lead to a rise in loneliness with fewer people participating in groups and helping their neighbors, higher health care costs , decreased economic growth, employment barriers, and less efficient government and business.

Ellen Szarleta, director of the Indiana University Northwest Center for Urban and Regional Excellence, has studied civic engagement as part of the civic index team for about 10 years.

Reviewing data from 2010 to 2023, Szarleta noted the state’s rank in volunteering rose from 32nd to 19th, while the rank for doing favors for neighbors rose from 43rd to 28th, and charitable giving rose from 45th place to 32nd place.

However, when comparing social-interaction data from 2017 to 2023, she found that Hoosiers were contacting family and friends far less frequently and not discussing issues with their neighbors as much.

Consuming news about politics and posting about political, societal or local issues on social media had fallen across all age groups from 2017 to 2023. The area of political participation that increased across age groups from millennials through baby boomers was buying or boycotting a particular product or service.

Szarleta found millennials and Generation X posted the most “significant declines” in volunteering, political involvement and group participation.

To improve Indiana’s civic health, Szarleta recommended expanding civic awareness throughout one’s life, so as Hoosiers age, they know about opportunities to remain engaged in their communities. Also, she suggested revitalizing public spaces within communities that enhance residents’ sense of belonging, including parks, libraries, museums, cultural centers, sports fields, trails, and town squares.

“We will have to commit to learning how to participate in meaningful and constructive ways,” Szarleta wrote in the 2025 index. “It will be a long-term commitment for the betterment of Indiana’s civic health.”

A bright spot in Indiana’s civic health is the state’s civic education programs and opportunities for students. Many young Hoosiers can engage in a range of activities in their schools and their communities, which can bolster their participation in elections and their contributions to the civic wellness of their cities and towns.

Stephanie Serriere, professor of social studies education at Indiana University Columbus, wrote the section on civic education in the 2025 index, outlining the programs that are building young people’s civic health and highlighting the areas of civic engagement where the youth are lagging adults.

“If civic health is understood as ‘the way that communities are organized to define and address public problems,’ then youth must be actively included in that equation,” Serriere wrote. “Civic engagement is not an innate skill – it must be cultivated early through both in-school and out-of-school experiences that allow young Hoosiers to engage in respectful dialogue, listen to differing opinions, and find common ground to address shared challenges.”

The programs and initiatives available to help young Hoosiers strengthen their civic skills include the We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution program, which, according to the 2025 index, impacts more than 10,000 students every year. Also students can participate in the Indiana Kids Election, Indiana Civics Bee and the Indiana YMCA Youth & Government program, which allows teenagers to take part in simulated legislative, judicial and media events.

Outside of the classroom, Hoosier youth can join leadership and service councils, such as those part of the Aim youth councils network, and help with elections as part of the Indiana secretary of state’s Hoosier Hall Pass, which allows 16- and 17-year-olds to serve as poll workers on Election Day.

Even with these opportunities, young people, ages 16 to 29, exhibit a markedly different level of civic engagement than adults, age 30 and older. Serriere pointed to data which shows Hoosier youth are “significantly more likely” to discuss political, societal or local issues with neighbors and share their views on social media, but they are “considerably less likely” to collaborate on community projects, attend public meetings or consume news.

Also, Serriere highlighted data from the Indiana Youth Institute. In 2025, young people in Indiana scored higher than their counterparts in neighboring states on social associations and matched the national average of 74.3% for participating in extracurricular participation.

However, the data also indicated that Hoosier children were less likely to participate in activities like music, dance, language and art lessons. Moreover, participation depended on parental education with children whose parents have only a high school education being more than six times less likely to join an extracurricular activity compared to children whose parents hold a college degree or higher.

“Disparities tied to parental education and lower involvement in arts and other organized activities highlight opportunities to expand and diversify civic engagement offerings,” Serriere wrote. “To promote more balanced opportunities for youth of all economic backgrounds, Indiana should prioritize increasing access to a broader range of extracurricular programs—especially in communities where participation is lagging.”

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org