By Rebecca Hill

The Indiana Citizen

November 12, 2025

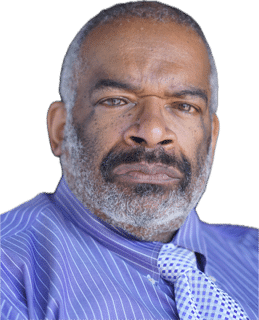

Riley Children’s Health pediatrician Dr. Eric Yancy has treated children with meningitis, sepsis, brain damage, and even one case of polio.

Giving vaccines is part of his practice, so he’s accustomed to discussing them with parents and their children, often with children present. Throughout, he’s explained why he believes that vaccines are essential and answered questions on autism, mercury, aluminum, and other concerns.

In 1979, Yancy found vaccine concerns from his patients were nonexistent. Then, in the mid-1980s, he began to face questions from parents about the DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccine.

But after the 1998 Lancet article that implied a link between the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and autism, those questions increased. Despite later being retracted by Lancet, the now-debunked medical study still causes problems.

“Pushback has continued since then,” Yancy said of opposition to vaccines. “I’m old enough now to have seen zero pushback to where it’s fairly common now.”

The result of the questions, confusion and refusals has been an ongoing decline in vaccination rates as some parents are deciding to either delay inoculating their children or forgo getting the immunizations altogether. Indiana’s vaccination rates have been declining since 2019, with an overall drop from 70% in 2019 (of children aged 19-35 months receiving a seven-panel vaccine series) to 62.2% in 2024.

In Indiana, legislation has been introduced – so far, unsuccessfully – in previous sessions of the General Assembly that has sought to expand the exemptions and allow more unvaccinated children into the classroom.

At the federal level, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, has upended staffing and committee appointees to elevate the voices of vaccine skeptics and has advanced unfounded theories about the causes of autism.

Efforts to counter those fears and make vaccinations available and convenient are also being stymied by funding cuts. The Trump administration cut federal COVID-19 era grant funding for national, state and local public health departments by $11.4 billion in March. A few months later, in May, Indiana legislators rolled back the 2024 public health funding boost for local health departments and the Health First Indiana program by $185 million.

While most parents genuinely want more information about vaccines, Yancy found that many were confused about what they had read or learned from family, friends, or social media.

Now into his fifth decade as a physician, Yancy continues to counsel reluctant parents. While he acknowledges the challenge of countering misinformation and disinformation online, he estimated his success rate at convincing adults to vaccinate their children is about 70% to 80%.

However, he has been seeing a new kind of resistance among some parents.

“There is nothing that I can say that will get them to take the vaccine, because not only are they totally against it, but they are totally against it for everyone,” Yancy said. “They want vaccines gone.”

The decline in vaccination rates has been linked to an ongoing outbreak of a disease considered eliminated in the U.S. since the year 2000: measles.

Riley Children’s Health pediatrician Dr. Shannon Dillon said she is focused on protecting young patients from the disease. In her office, pediatric teams and administrators have had discussions about preparing for and managing any suspected case of the measles. The goal has been to minimize any potential exposure, especially for those patients who are immunocompromised or being treated for cancer.

“It’s alarming,” Dillon said. “All of us who do primary care and who treat sick kids only have to look at the number of measles cases that we are now seeing this year. (The number of cases has) been the highest they have been for at least 20 years.”

As a childhood disease, measles is often seen as a rite of passage, where most who get it survive. Yet, measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus that is spread through respiratory droplets from person to person and can induce a fever, runny nose, cough, and a tell-tale rash that begins on the face and neck. Infants and young children are especially susceptible to contracting and dying from the disease. The Lancet Infectious Disease Journal reports that one person can potentially infect 12 to 18 other people.

As of November 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 1,681 confirmed measles cases in the U.S. with 12% of those cases requiring hospitalization, and 26% of the cases occurring in children under the age of 5. The CDC reports that 92% of these occurred in patients who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown The disease has been reported in 41 states, including Indiana, where 11 cases have been reported this year.

Allen County has been the hardest hit in the state so far this year with eight reported cases of

measles, according to the Allen County Health Department. Five of those were unvaccinated minors, and three were adults whose vaccination status was unknown.

Dr. Tony GiaQuinta, a pediatrician at Parkview Health’s Alliance Health Care in Fort Wayne and nephew of Indiana House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta, has treated several measles cases during the outbreak this year. Practicing since 2012, GiaQuinta has recommended vaccines to thousands of his patients as well as his own children and those of his relatives, but now his clinic is seeing a spike in vaccine-preventable diseases.

The first measles vaccine was licensed in the United States in 1963 and in 1971, it was combined into a vaccine that also prevented mumps and rubella, according to “History of Measles” in the September 2022 issue of ScienceDirect. By 1978, the single-dose MMR vaccine was introduced which led to a 90% drop in the number of measles cases, although epidemics still occurred every 3 to 5 years. After a national program using the two-dose measles vaccine was implemented, the number of cases fell dramatically and by the year 2000, endemic measles had disappeared from the United States.

For Indiana kindergartners receiving the seven-panel vaccine series during the 2024-25 school year, the rate was 90.6%. The U.S. rate for kindergartners was 92.5%. The HHS’s Healthy People 2030 framework for improving health in the U.S. has an MMR target rate of 95%.

While these drops might not seem significant, other states are also experiencing similar drops that cumulatively impact the communities’ ability to reach herd immunity, a condition defined by the American Medical Journal as when “a significant portion of the population becomes immune to an infectious disease, causing the risk of person-to-person spread to decrease” after which further spread of a disease is limited.

Ironically, the success of the vaccines may be fueling parents’ decisions to skip inoculations. As measles and other childhood diseases have waned because of vaccinations, people have become complacent about getting their youngsters immunized, believing that the diseases are no longer a threat.

Immunizations are “victims of their own success,” Yancy, at Riley Children’s Health, said. “Very few people have actually seen a child with polio. If you haven’t seen it, you don’t fear it, the same being true about the recent measles outbreaks.”

Contributing to the rise in preventable diseases like measles and whooping cough (pertussis) is vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy is a refusal or delay in acceptance of a vaccine, as compared to someone with an anti-vaccine agenda.

GiaQuinta, of Alliance Health Care, has seen a 10%-15% rise in vaccine hesitancy in the past three to five years. “I am deeply concerned.,” he said. “I have patients and their families wanting to spread out (vaccine schedules) or withhold vaccines. Unfortunately, this means that their children will be at a higher risk for vaccine-preventable diseases,.”

In fact, a 2015 Pediatrics study found that 87% of pediatricians believed that spreading out a vaccine schedule put children at risk for disease, and 84% thought it to be more painful for children. Yancy said that because each immunization, especially for infants, builds on the previous one, spreading those vaccines out “actually delays a child’s full protection for maybe a couple of years.”

Vaccine hesitancy is clearly one of the drivers behind the lowering of immunization rates. The World Health Organization has listed vaccine hesitancy as a top threat to global health, saying vaccines prevent 2-3 million deaths a year and could avoid 1.5 million more deaths if their global use improved.

The Journal of Behavioral Medicine examined barriers to vaccination and found that the following factors contributed to vaccine hesitancy: low knowledge about vaccines, concerns about side effects, misinformation and disinformation, social networks and peers, media portrayals, medical mistrust, political affiliation, and science skepticism.

Sara Burnett, a public health nurse for the Putnam County Health Department, started to see a rise in vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s her job to educate her community’s residents about the effectiveness of vaccines, but she says that grew more difficult after the pandemic.

“COVID ruined it for us (the health department), and vaccines became a lot more controversial in Putnam County,” Burnett said. Now she promotes vaccine data and research, including demonstrating how vaccines work in an ongoing battle against vaccine hesitancy and misinformation. “I wouldn’t be a nurse if I didn’t believe in science,” she said.

On June 9, 2025, the Associated Press reported that HHS Secretary Robert Kennedy Jr. fired all 17 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which sets immunization schedules for adult and childhood vaccinations. Kennedy is accused of replacing the former ACIP members with new ones who were vaccine-hesitant and spread misinformation, a move that caused leading medical societies and organizations to strongly object to the ethical and professional makeup of the council

Since then, Kennedy, a longtime vaccine opponent, has argued that MMR vaccines cause autism, that Tylenol causes autism, and even that the dose of Tylenol given to infants after circumcision can cause autism, demonstrating how far Kennedy has extended his unsubstantiated rhetoric regarding vaccines. Kennedy’s claims about the pain medication have been repeatedly refuted by physicians and medical associations.

On October 11, Forbes reported that Kennedy also fired over 1,000 employees who had collected data and managed infectious disease outbreaks at the CDC, although some have since been rehired.

However, Heather Pfingston is relieved to see RFK Jr. is leading the nation’s public health effort.

For the Bloomington mother, the vaccination process was complicated, even intimidating. Today, she regrets vaccinating her daughter. Now her grown daughter is considering whether to vaccinate her children. In the 1990s, “I was a very young mom having had three children by age 21, so I was naïve and easily manipulated,” Pfingston said. “I did question what was in the vaccines and was absolutely pressured and strong-armed.”

When Pfingston asked her doctor what would happen if she opted her children out of the MMR vaccine, “I was told that because of the oath they took as a doctor, they would be ‘forced’ to call (the Indiana Department of Child Services),” Pfingston said.

Pfingston then cited a list of ingredients that she now believes are in vaccines and said she might have fought back harder against her doctor if she had known the contents of the shots.

All vaccines contain trace ingredients that stabilize, preserve, and help trigger immune responses, but vaccines like the flu vaccine do not contain traces of shark liver oil, pig and cow gelatin, monkey kidney cells, or even fetal human cells. Cells are needed to grow the virus and human cells have been used to determine which cells a virus will infect. In the early 1960s, scientists used fetal cells taken from two elective pregnancy terminations at that time. However, no new fetal cells have been used since that time and, as a result, vaccines no longer contain fetal cells.

Now Pfingston feels like her daughter has more options and she credited RFK Jr. and what she called “his efforts to bring not only transparency about each vaccine, but also (information) in layman’s terms.”

An Indianapolis mom, Taylor Stucky, has two children and has vaccinated both. Despite this, she also had concerns and moments of hesitation as to whether she was making the right decision. “There is so much noise online,” she said. “But I did my research and talked it through with our pediatrician.”

Her pediatrician took the time to explain the “why” behind current recommendations, so Stucky felt that having someone she could trust and who was knowledgeable on vaccines made her feel more comfortable and confident in her decision to inoculate her children.

However, Stucky and other Hoosier parents may face confusion in the future, as they search for information and answers to their questions.

Kennedy’s changes to the HHS have resulted in changing vaccination requirements, which in turn, has caused some medical associations to take the unprecedented step of offering their own guidelines that differ from those of the government.

Medical societies such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Cardiology, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, along with at least 22 states, have formed their own vaccine schedules or identified outside sources for vaccine recommendations.

As an example, federal recommendations have previously called for children to be administered two doses of the MMR vaccine. The first dose should be given when children are 12 to 15 months of age and the second when they are 4 to 6 years old. Now the immunization guidance has changed. As of September 2025, the ACIP no longer recommends the combination MMR vaccine.

However, the American Academy of Pediatrics is sticking to the previous recommendations. The AAP is advising that children receive two doses of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine or the measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (MMRV) vaccine with the first dose administered at 12-15 months and the second dose at 4-6 years.

Traditionally, the Indiana chapter of the AAP’s vaccination schedule aligned with the ACIP’s schedule. Will the Indiana chapter follow the AAP’s recommendations?

“It is very rare that we would not align our views with the national association,” said Christopher Weintraut, Indiana’s president. “It is only in those rare cases of deviation where we might choose to publish our position and provide an explanation for any deviation from the national AAP’s position. I do not anticipate that happening in this case.”

Yancy, the Riley Children’s Health pediatrician, is adamant that following the AAP’s science-based data and recommendations is critical.

“You can’t tell me that you just one day come in and fire everybody and say, ‘well, everyone here is bad, let’s get rid of everyone,’ then replace them with those who are known to have anti-vaccine backgrounds,” Yancy said. “I fully support AAP’s position on scheduling. We can’t really risk a child’s health on what might be OK. We already know what’s OK.”

To add to the chaos, the Trump Administration cut federal COVID-19 era grant funding for federal, state, and local public health by $11.4 billion in March. A September 2025 study by the Milken Institute School of Public Health of George Washington University found that Indiana would lose $37.5 million in CDC funding and $28.2 million in CDC grant funding. This would equate to $52 million in state GDP lost, 567 jobs lost, and $2.4 million in state and local taxes lost.

In May, Indiana legislators rolled back 2024 public health funding for local health departments and the Health First Indiana program $225 million in the previous two-year budget to just $40 million in the current budget. This funding loss has impacted immunization practices across the state.

As a result, the Marion County Health Department lost programs, reducing funding from $22.7 million to $6 million, and lost a $454,000 immunization grant from the CDC. Allen County funding went from $8.98 million to $2.4 million. Putnam County’s Health Department Administrator Joni Young said that “they have had to cut all of our immunization educational outreach and off-site vaccinations due to funding.” Their 2025 funding was cut from $716,157 to $192,040 for 2026.

All these actions are now contributing to an atmosphere of confusion and distrust, affecting not only parents but also physicians and health providers, and fueling the current decline in immunization rates.

The Indiana Immunization Coalition hosts underserved rural health and vaccination clinics throughout the state, focusing on preventing the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases in Indiana. Last year, they administered 58,263 vaccines at more than 320 clinics and provided resources and education to local health departments and health-care providers.

But the cuts in March 2025 to COVID-19 era funding resulted in an 80% loss of their federal funding. They are now limiting the number of immunization clinics they can hold due to funding cuts.

For Sara Dillard, IIC communications director, the list of concerns is growing.

“Misinformation is skyrocketing. We are getting more outbreaks,” said Dillard. “We are literally looking at coming into a perfect storm.”

Riley Children’s Health nurse and mother of two, Jaquelyn Felling, has long seen the value of vaccines as an oncology nurse and has seen kids at risk for infection and who are immunocompromised. Her best friend decided not to vaccinate her own children, which made for a difficult conversation with her.

“When she was making the decision, she asked me what I thought about vaccinations,” Felling said. “I told her that they were essential for the community and that they had done great things for children.” Her friend then asked her, “If your kids are vaccinated, why are you afraid of my kid?” Though she respects her friend’s decision, Felling does acknowledge that they have a difference of opinion.

Felling now worries that vaccine skepticism is contributing to declining immunization rates in Indiana.

“It’s getting more and more popular not to vaccinate,” Felling said. “I feel like now is the worst time for that to happen.”

Rebecca Hill has been a medical and science journalist for 18 years. She is a former medical and science writer for Limestone Post Magazine in Bloomington and has contributed to other local and national publications.

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org.