By Sydney Byerly

The Indiana Citizen

February 9, 2026

A conservative split over syringe exchanges is resurfacing this year, with Indiana Republicans invoking faith — and reaching drastically different conclusions — as they consider whether to extend the state’s existing policy for another decade.

A House committee on Tuesday morning is scheduled to debate Senate Bill 91, which would allow counties to continue running syringe services programs through 2036. Those programs were first launched in the wake of an HIV outbreak in Scott County in 2015, when then-Gov. Mike Pence, facing mounting pressure to address the historic, drug-fueled outbreak, dropped his long-held opposition to syringe exchanges and supported legislation to allow local officials to operate them.

If the General Assembly doesn’t act, services that provide clean needles and dispose of used syringes, now in place in six counties, would be forced to shut down on June 30.

The Senate approved the bill on a 33-13 vote last month. But supermajority Republicans were split, accounting for all of the “no” votes — revealing a party once again divided over whether providing clean needles to drug users is an act of mercy or moral surrender.

Supporters argue that allowing local syringe services saves lives and connects people to care, while opponents warn they normalize drug use — a divide that echoes the state’s HIV crisis a decade ago, when more than 230 people became infected in the rural southern Indiana town of Austin.

People backing the bill said its fate in the House, where Republicans also hold a supermajority, is uncertain because it’s not clear whether several GOP members of the House Public Health Committee will vote to advance it to the full chamber.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, syringe service programs reduce HIV and hepatitis C infections by about 50%. But they remain controversial — including in Scott County, where in 2021, county commissioners voted 2-1 to end the program there. The commissioners who voted to end the program said at the time they didn’t want to make it easier to use drugs.

Opposition to extending Indiana’s syringe exchange program is being led publicly by Lt. Gov. Micah Beckwith, a self-described Christian nationalist who has framed the program as a moral failure rather than a public health necessity.

In a series of posts on social media following the bill’s passage in the Senate, Beckwith — who also serves as a pastor at Life Church in Noblesville — condemned the legislation in explicitly religious terms.

“The Road to Hell is Paved with Good Intentions,” Beckwith wrote in one post, criticizing what he described as a “syringe exchange GIVEAWAY.”

Beckwith wrote: “We don’t ‘heal’ addictions by forcing hardworking taxpayers to bankroll needles for hard drug users. That’s not compassion; it’s reckless enabling that traps people in cycles of destruction.”

Beckwith also criticized the bill for not mandating a strict one‑to‑one syringe exchange requirement, arguing that it relies too heavily on “hope and prayer” that local governments impose safeguards.

He urged House Republicans to reject the bill as it moves forward, saying “SB91 is not good and it’s not Hoosier values. Hoosiers help, not enable.”

Beckwith’s office did not respond to multiple requests for an interview to discuss his position in more depth.

Former Indiana Attorney General Curtis Hill, another Republican, echoed Beckwith’s criticism during a podcast interview hosted by the lieutenant governor. Hill, who served as attorney general from 2017 to 2021, said he opposed syringe exchange programs while in office and often disagreed with former Gov. Eric Holcomb’s administration over keeping them in place.

“The suggestion was that if you give people clean needles, that somehow dissipates the problem,” Hill said on the podcast, “I pointed out that’s not true. If you take a dirty needle away and give them a clean needle, they’re still injecting this stuff into their system, still subject to overdose.”

Hill acknowledged that syringe exchange programs can reduce the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, but argued that they fail to address overdoses and may worsen the broader drug crisis by involving the state in what he described as enabling dangerous behavior.

“If your objective is to stop overdoses, and you’re still giving needles to people to potentially overdose, you’re certainly not doing what it was supposed to do,” Hill said.

But other conservatives — including public health leaders, lawmakers, and policymakers who say their actions are informed by their faith — argue that extending syringe exchange programs is not a rejection of moral responsibility, but an expression of it. They point to a decade of data from Indiana and beyond showing the programs reduce disease transmission and connect people to treatment.

Former U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, a Republican who served as Indiana’s state health commissioner under Pence during the Scott County outbreak, said the past decade has provided lawmakers with clear evidence about what syringe services programs do — and what they do not do.

“These are some of these same concerns that were raised a decade ago, and while I understand and respect people’s concerns, I would respectfully disagree with the lieutenant governor framing this as hope and prayer,” Adams said of Beckwith.

“The reality is, we actually have more than hope and prayer,” he said. “We have 10 years of data to go on, and I would hope that the legislature would look at that 10 years of data and the success that we’re finally having in turning around the opioid epidemic and make a decision that is based on the actual data, and not on fear and speculation.”

But, he added: “We know the sky didn’t fall in communities that initiated syringe services programs, and we know that these programs … really do have a track record of connecting people to care.”

Supporters of SB 91 also point to research showing that syringe services programs reduce the sharing of needles associated with HIV transmission and lead to fewer improperly discarded syringes in public spaces. Studies have also found that ensuring sufficient access to sterile syringes — rather than limiting supply through strict one‑to‑one exchange requirements — is associated with better public health outcomes.

Data compiled by ProtectSEP.org indicates that syringe exchange programs result in eight times fewer discarded needles in public places and reduce the risk of accidental needle sticks to law enforcement officers by 66%. Researchers say those findings directly challenge the idea that syringe services programs increase needle litter or endanger communities.

Dr. Beth Meyerson, a former faculty member at Indiana University School of Public Health and researcher at the University of Arizona, who studied Indiana’s syringe services programs for years, said concerns about increased drug use or needle litter are not supported by evidence.

Meyerson’s research has found that syringe services programs reduce disease transmission, protect first responders and serve as entry points to testing, treatment referrals and overdose prevention services.

Peer‑reviewed studies support those conclusions. A 2019 study found that participation in syringe services programs was associated with reduced risky injection behaviors linked to HIV transmission. Another study documented a nearly 50% reduction in improperly discarded syringes in public spaces after the implementation of a syringe services program.

Other opponents have focused less on morality and more on public safety and oversight.

During committee testimony in early January, Christopher Daniels of the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council warned of unintended consequences.

“Our concern is the unintended consequences that when trying to fix one problem in one space, we create another problem in another,” Daniels said. “One of our major concerns being the lack of one‑to‑one exchange in a lot of these needle programs, which results in a proliferation of needles in communities.”

Supporters counter that public health experts do not consider strict one-to-one exchange models necessary for syringe services programs to be effective. Research has shown that ensuring sufficient access to sterile syringes — often referred to as adequate syringe coverage — is associated with lower rates of HIV and hepatitis C transmission and fewer improperly discarded syringes in public spaces.

Some public health officials also note that one-to-one exchange requirements can create safety risks for program staff by requiring direct handling of used needles. Instead, many programs track returns by weighing sharps containers before and after disposal and estimating syringe counts based on weight — a method intended to reduce occupational exposure while still monitoring program use.

Fiscal questions have also surfaced.

Sen. Liz Brown, R‑Fort Wayne, one of just two committee members who voted against SB 91, repeatedly asked during testimony how syringe services programs are funded and whether taxpayer dollars support them.

The bill, in its current form, does not create a new state-funded program or require taxpayer dollars to be spent on syringe services. Instead, funding decisions for syringe services programs are made at the local level, typically supported through a combination of local health department resources, federal public health grants, private foundation funding and partnerships with hospitals or nonprofit organizations.

Extending the authorization, lawmakers in support of the bill argue, allows local governments to respond to public health conditions without requiring state funding or participation.

The current divide echoes the battle that erupted during Indiana’s 2015 HIV outbreak, when conservative leaders wrestled with whether needle exchanges conflicted with anti-drug policy or aligned with their Christian duty to protect life.

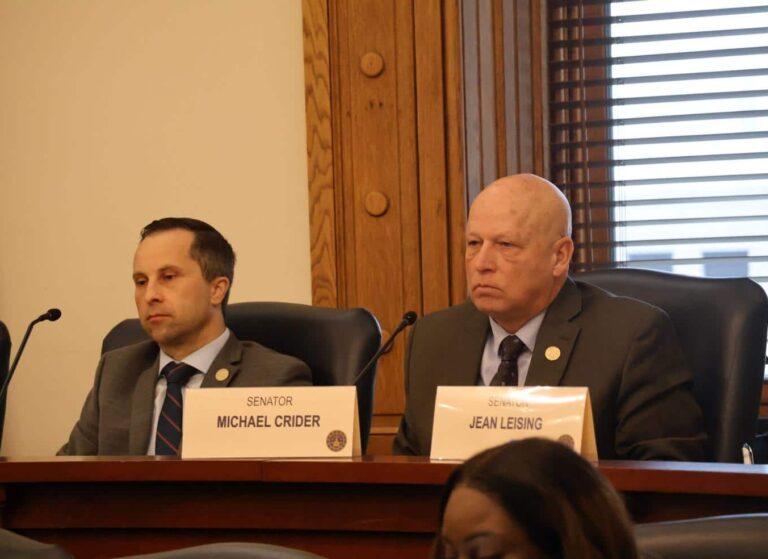

Sen. Michael Crider, R-Greenfield, one of SB 91’s authors, said his support for the bill is rooted in both professional experience and personal encounters with addiction.

“I carried the bill in the past, and so I’m familiar with how important the syringe services program is to folks that find themselves in the addiction space,” Crider said. “When I retired from law enforcement and worked in hospital security, I began to understand that people aren’t using drugs to get high anymore — they’re using to not be sick.”

Crider said the goal of syringe services programs is to reduce harm while connecting people to treatment.

“If we can keep them from reusing needles and keep them from sharing needles, then we benefit not only them and their family, but police, fire, EMS and health care workers,” he said. “Most people think it’s enabling. I don’t think they actually understand addiction.”

Crider added, “If we can keep people healthier than they might have been otherwise, that’s a good thing,” he said. “For me, this is pretty easy.”

Rep. Ed Clere, a long-time Republican legislator who is running for New Albany mayor as an independent and a House sponsor of SB 91, said the current debate feels like a replay of the political battle during the Scott County HIV outbreak — a fight that ultimately cost him his chairmanship of the House Public Health Committee.

“The syringe legislation in 2015 remains the toughest and costliest battle that I have fought in my 18 years in the legislature — but I would do it again, because syringe service programs have saved countless lives, prevented countless cases of infection and connected numerous people with recovery programs and other resources that have saved and changed lives,” Clere said. “When syringe exchange started in Scott County, the spread of HIV all but stopped.”

Clere called SB 91 “absolutely critical legislation,” warning that without it, all six remaining syringe services programs would be forced to shut down after June 30. The six active programs are in Marion, Monroe, Clark, Tippecanoe, Allen, and Fayette counties.

“We learned in 2015 that nowhere in Indiana is very far from [being another] Scott County,” Clere said. “Syringe service programs have saved countless lives, prevented countless infections and connected countless people with recovery resources.”

Indianapolis Democrat Sen. La Keisha Jackson, a co‑author of the bill, framed syringe services programs as part of a broader harm‑reduction strategy. She has said such programs often provide one of the few points of contact between marginalized populations and the health care system, offering access to testing, treatment referrals and overdose prevention resources.

Faith played a central role in Indiana’s syringe exchange debate a decade ago — and it continues to shape the conversation today.

During the Scott County outbreak, Pence, a socially conservative Republican, initially opposed needle exchange programs, describing them as incompatible with anti‑drug policy. Pence later said prayer and mounting evidence led him to reconsider, ultimately authorizing emergency syringe exchanges as the outbreak spread. Still, researchers and public health officials have argued that Pence’s delay in 2014 and 2015 lead to cases that could have been prevented.

Adams said faith and evidence ultimately converged during the Scott County crisis — and can do so again.

“We know overdose rates are starting to go down,” Adams said. “And we know these programs connect people to care. That matters.”

Sen. La Keisha Jackson, a co‑author of the bill, said her support comes from years of seeing syringe services programs work at the local level while she served on the City-County Council in Indianapolis.

“I saw the promising effects,” Jackson said. “If it can save lives and offer people an opportunity to improve their quality of life until they can get treatment, then that matters.”

Jackson said the debate often fails to humanize people struggling with substance use.

“Until you hear from people who are actually living this life — or their families — you can’t judge it from the outside,” she said. “It’s like the saying until you walk a mile in my shoes. We have to get to the root cause and treat people in a humane way.”

Supporters of SB 91, like bill author Crider, says faith informed support for these services just as deeply as it has shaped opposition.

“The Bible I read says the two greatest commandments are to love God and love your neighbor as yourself,” he said. “Sometimes your neighbor is a guy living under a bridge with a needle in his arm. My faith demands that I try to help people who find themselves in a really tough spot.”

Sydney Byerly is a political reporter who grew up in New Albany, Indiana. Before joining The Citizen, Sydney reported news for TheStatehouseFile.com and most recently managed and edited The Corydon Democrat & Clarion News in southern Indiana. She earned her bachelor’s in journalism at Franklin College’s Pulliam School of Journalism (‘Sco Griz!).

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org.