By Sydney Byerly

The Indiana Citizen

December 10, 2025

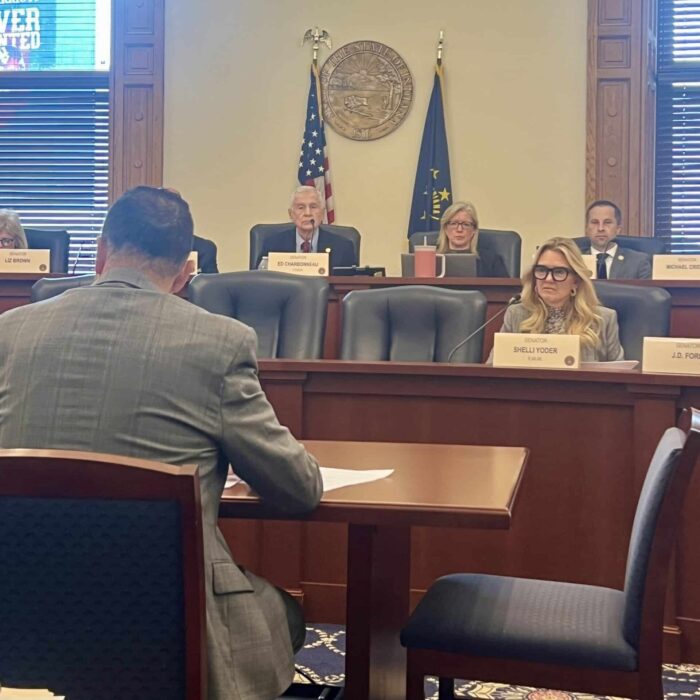

The Senate Health and Provider Services Committee kicked off its meeting Wednesday with a familiar debate: how to rein in hospital medical debt practices without upending the state’s health care system.

But after two years of work, lawmakers admitted they’re still searching for an elusive “sweet spot.”

Senate Bill 85, authored by Sens. Ed Charbonneau, R-Valparaiso, and Fady Qaddoura, D-Indianapolis, would require hospitals to offer payment plans to certain low- and moderate-income Hoosiers, limit wage garnishment for qualifying patients and prohibit placing liens on primary residences for unpaid medical bills. The bill also mandates more transparency, including written notices about charity care programs and clearer financial-assistance information on billing statements.

Supporters say the goal isn’t to erase what people owe but to ensure a medical emergency doesn’t turn into a financial crisis that threatens a family’s stability.

Qaddoura, who introduced the bill, said after a similar medical debt bill failed in the 2025 legislative session, he and Charbonneau went back to the drawing board to update the measure.

“It’s an issue that needs to be dealt with,” Charbonneau said.

However, he also nodded to the difficulty of tackling an issue lawmakers failed to address last year amid opposition from hospitals and collections agencies.

“The product that we discussed today is well done,” Charbonneau said after the hearing. “But whether or not it’s enough — there are a lot of parties that are playing in this arena, and we’re just going to have to continue to work at it.”

The committee will not meet again until January 2026, but Charbonneau expects it to meet at least two or three times in the first half of the regular session. It’s not yet clear when the committee will vote on the measure.

The burden of medical debt in Indiana is massive. According to a report by Indiana Community Action Poverty Institute, nearly one in five Hoosiers has medical debt in collections — amounting to an estimated $2.2 billion statewide. Such debt has pushed families to choose between basic necessities and past medical bills, and advocates warn many Hoosiers delay or skip care because of overwhelming bills.

The push to address the issue traces back to a similar measure introduced last year, Senate Bill 317, authored by Qaddoura. That bill attempted to limit wage garnishment and prohibit placing liens on primary residences for unpaid medical debt among low-income Hoosiers, but it narrowly failed in the full Senate by a 26–23 vote.

After the defeat, lawmakers — at the urging of House Speaker Todd Huston — agreed to use the interim period to dig deeper into the problem. The Legislature’s Indiana Legislative Council assigned the topic to an interim study committee led by Sen. Liz Brown, R-Fort Wayne, which spent the summer and fall of 2025 gathering testimony, data and feedback. The committee looked into how hospitals define charity care, how payment plans are offered, how debt collection and wage garnishment are currently handled and how often payment-plan options actually reach patients. The study committee didn’t issue any recommendations, though, and Brown said it didn’t receive enough information from hospitals on charity care and payments systems.

Qaddoura walked the committee through several revisions aimed at addressing concerns raised during a summer study committee focused on the issue:

Qaddoura said Indiana courts have seen “an increase in medical debt cases,” calling the burden unique compared to other forms of debt.

“No one chooses to have cancer or ALS,” he said. “Even if you’re fully insured privately through one of these insurance companies, by the time you pay your deductibles and you pay your out of pocket expenses… you have to pay 15 to 20, $25,000 out of pocket before you get 80, 90% coverage of your insurance.”

Erin Macey, director of the Indiana Community Action Poverty Institute, told the committee that allowing Hoosiers to get the health care they need without facing additional financial hardships is “a worthy goal.”

“We’re not seeking to erase medical bills,” Macey testified. “We’re trying to make repayment manageable for low- and moderate-income Hoosiers who are navigating other pressures on their household budgets.”

Judy Fox, professor emeritus at Notre Dame Law School, who has studied medical debt for decades, urged lawmakers to refine the garnishment language and broaden the statutory definition of medical debt.

Tiffany Nichols, director of advocacy for the American Lung Association, underscored the scale of the problem, saying nearly 20 million Americans hold medical debt, including more than 600,000 Hoosiers.

“Three in 10 adults who already owe medical debt cannot pay an unexpected bill of just $500,” she said.

Dave Almeida, government affairs director for Blood Cancer United and speaking on behalf of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, highlighted the research that has been done to evaluate the experience and challenges cancer patients face. In particular, he said, the two conclusions that were most concerning were that cancer patients incur a lot of medical debt that they do not think they can repay and they are making treatment decisions based on that debt.

“They were foregoing treatment,” Almeida said. “They were not going back to the same providers where they owed money. Their medical debt had become an impediment to them getting better treatment.”

Jane Hartsock, vice president of the Good Trouble Coalition, framed the issue in seasonal terms.

“There are families in this state who are choosing right now between presents under the tree and paying on their medical bill,” Hartsock said. “This bill serves both the identifiable, demonstrable needs of Hoosiers and the spirit of this time of year.”

Representatives from the American Collection Association delivered the sharpest critique, arguing that the bill lacks income-verification requirements and could allow patients to self-report earnings without documentation and commit fraud. They also noted that hospitals have no investigative authority to validate claims.

Their testimony drew a sarcastic response from Sen. Mike Bohacek, R-Michiana Shores. “It’s frightening. I didn’t know the whole hospital industry was going to collapse under the weight of this burden,” he said.

The Indiana Hospital Association also raised objections. Its government relations vice president, Luke McNamee, warned that the bill creates a “one-size-fits-all approach” to payment plans and eliminates the ability to negotiate individualized terms.

“Hospitals exist to provide care for patients while finding ways to be compensated for those services,” McNamee said.

Several lawmakers asked how the bill would affect different populations and hospital practices.

Sen. La Keisha Jackson, D-Indianapolis, said she wants more assurance that seniors on median incomes would qualify. She also emphasized the need for hospitals to better publicize charity care, sharing a personal story of a family member whose transplant-related bills were alleviated only because someone happened to mention the program.

Brown, the Fort Wayne Republican, had questions about what ramifications could be for someone who might fall within the coverage of the current language of the bill and decides not to take payment plans, but then doesn’t pay their bill.

The bill as it stands doesn’t contain any language specifically that touches on Brown’s questions.

Speaking to The Indiana Citizen afterward, Charbonneau said he expected a lot of testimony on the first day.

He also noted inconsistencies among the collection agencies themselves.

“One of them reports stuff to the credit agencies, the other one said they don’t,” he said. “With 60 of these agencies around the state…[all in all] we just need to find out what the facts are.”

After hearing from the hospitals and collection agencies, Charbonneau said the committee still had work ahead.

“We’ve been at this for two years, looking for a sweet spot to land,” he said. “I take it from your testimony, we haven’t found that sweet spot yet.”

Sydney Byerly is a political reporter who grew up in New Albany, Indiana. Before joining The Citizen, Sydney reported news for TheStatehouseFile.com and most recently managed and edited The Corydon Democrat & Clarion News in southern Indiana. She earned her bachelor’s in journalism at Franklin College’s Pulliam School of Journalism (‘Sco Griz!).

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org.