By Steve Hinnefeld

The Indiana Citizen

July 25, 2025

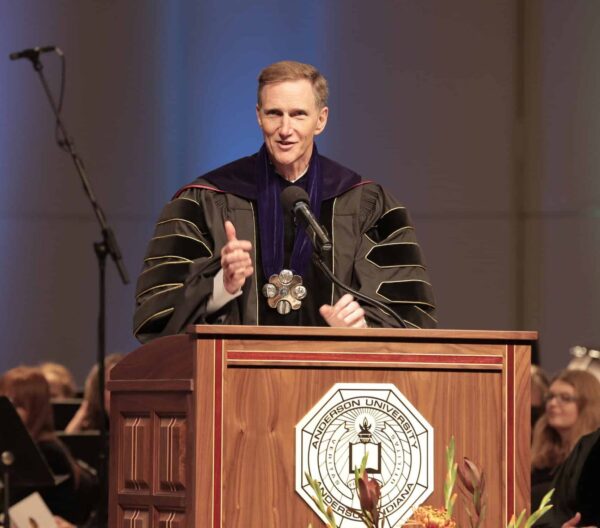

John Pistole spent a decade as a university president, retiring this year with a legacy of adding in-demand academic programs, increasing funding and growing enrollment at Anderson University. He admits things might be more difficult if he had started his tenure today.

In recent months, U.S. higher education seems to have faced one crisis after another. President Donald Trump has seemingly gone to war with elite universities, especially in the Ivy League. Gov. Mike Braun and other officials are reshaping higher education in Indiana.

“There’s a lot going on in higher education these days, so much of it tied to the uncertainty of what is the future of higher education in the U.S.,” Pistole said in an interview with the Indiana Citizen. “How do we navigate that? I think the answer, in one word, is cautiously.”

Today’s university leaders, he said, must not only have strong academic or business leadership credentials, they also must be sensitive to changing politics and they must be flexible and able to adapt quickly to new expectations.

Pistole stepped down as Anderson University president this summer. In June, he joined the Noblesville-based law firm of Church Church Hittle + Antrim as a senior adviser in its higher education practice group. Before his university tenure, he was the administrator of the federal Transportation Security Agency in the Obama administration. Prior to that, he was with the FBI, rising to deputy director under President George W. Bush.

Pistole grew up a block from the Anderson University campus and earned his undergraduate degree from the school before completing his J.D. degree at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. But he had never thought about being a college administrator and was stunned when a law school classmate suggested he consider the presidency. He discussed the idea with his wife, Kathy Harp, and they concluded it was an opportunity that God was providing.

“We pray for guidance and discernment every day,” he said. “”And so it just seemed like, if it does work out, then shouldn’t we be open to it?”

He’s had no regrets, but he admitted there were adjustments after working in government for 31 years. New to the university presidency, he wanted to offer degrees in cybersecurity and national security, his areas of expertise. The provost, Marie Morris, advised that he needed to first consult with the faculty.

“She kind of looked at me and said, ‘Well, are you planning to teach the courses? Are you planning to grade all the exams? Are you planning to be their adviser?’ And she was saying it with a little smile, like, welcome to higher education.”

But faculty worked hard to create the degrees, he said, and both were offered within 18 months. Anderson and its cybersecurity program have been designated as a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Defense (CAE-CD) by the National Security Agency.

Faculty roles aside, Pistole said that most U.S. university leaders could, until recently, count on clarity and some consistency about what was expected by federal and state policymakers. Regulating education, especially higher education, usually wasn’t a top priority.

“I don’t want to say it’s been hands off,” he said, “but the federal government and state governments, to a large degree, as long as there wasn’t a scandal or something really bad happening, they let the colleges and universities do their thing.”

Trump upended that approach. He issued executive orders banning diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, programs, warned institutions that they must crack down on antisemitism in campus protests and froze research funding. The administration canceled visas for at least 800 international students, some of whom had been involved in pro-Palestine protests. It blocked Harvard from adding international students and scholars, a decision that has been put on hold by a federal judge.

Some institutions resisted, even challenging the Trump administration in court; others have complied. As The New York Times reported, “University administrators are debating whether to freeze existing programs, stand on principle and resist, or try to fly below the radar while they see if the executive orders hold up in the courts.”

Several university presidents have resigned or retired under pressure. At the University of Virginia, a highly regarded state university, President James Ryan stepped down in June under pressure from the Trump administration, state officials and conservative alumni. The U.S. Justice Department reportedly demanded that he resign to resolve complaints that the university’s support for diversity, equity and inclusion violated civil rights laws.

Columbia University agreed on July 23 to pay over $220 million to settle allegations that it was soft on antisemitism to restore its federal research funding. That kind of deal-making might fend off the government, Pistole said, but it could upset donors who thought their values aligned with the institution’s. “If I was a seven- or eight-figure donor to Harvard or Columbia or UVA or Penn … would I make another gift if that’s where the money’s going to go?” he asked.

In Indiana, the General Assembly passed restrictions on diversity initiatives, leading some state institutions to scrap programs and scrub DEI references from their websites. Republican leaders in the General Assembly added a last-day budget amendment that reined in faculty influence and allowed Braun to appoint all Indiana University trustees. Lawmakers also called on state universities to eliminate degree programs with few students enrolled; six universities said they will cut or merge 400 programs.

“I think it’s reflective of what’s happened at the national level, where a chief executive is exerting more control and authority,” Pistole said. “There’s a dynamic tension between the governance by the trustees, who have responsibility to ensure the well-being of the university, versus the new sheriff in town, if you will, a governor who’s exercising more control.”

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, meanwhile, has extended the fight against diversity to private institutions. In recent months, he wrote to the University of Notre Dame and Butler and DePauw universities, warning their DEI policies could be illegal and may possibly face legal challenges.

Anderson University, a Christian University with 1,200 students that is affiliated with the Church of God, hasn’t promoted DEI the way some schools have. But the news release announcing Pistole’s retirement said he had “implemented programs to increase diversity among students, faculty, and staff and … improved the university’s diversity metrics.”

Pistole, while emphasizing that he doesn’t speak for Anderson, said the school’s support for diversity and inclusion is about “being a Christian university where we try to live out the ethos of, how did Jesus welcome and invite people into relationship? He welcomed the stranger and those who might not be in favor.”

Being known as a place of welcome may be increasingly urgent for universities, when many people question the value of a college education. A recent study for the Indiana Commission for Higher Education found that 80% of Hoosier students and parents believe continuing education beyond high school is worthwhile. Independent Colleges of Indiana, of which Anderson University is a member, says that private colleges contribute at least $5.5 billion a year to the state’s economy. But barely half of Indiana’s high-school graduates enroll in college; the state’s college-going rate has decreased more than any other state’s, according to federal data. Only 45% of male high school graduates enroll in college, compared to 59% of female students. Some students may say college is still worthwhile, but many others are now “voting with their feet” to say it isn’t.

Pistole said it’s healthy that colleges and universities are having to assess their relevance and make the case that they’re providing something of value. But the trend away from college-going will make it difficult for some institutions, especially small private colleges, as they also face a demographic cliff of fewer 18-year-olds.

“I think that’s one of the great challenges for both the private and public institutions in Indiana,” he said, “to continue to navigate this continuing trend.”

Steve Hinnefeld is a freelance writer based in Bloomington. He formerly was an adjunct instructor at the Media School at Indiana University, a media specialist at Indiana University and reporter for the Bloomington Herald-Times.

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.