By Marilyn Odendahl

The Indiana Citizen

February 6, 2026

A provision in Senate Bill 291, preventing the disclosure of personal information about state judges and justices, drew a second look from some legislators during a House committee hearing on Wednesday and is causing one First Amendment expert to question the intent of the language.

Authored by Sen. Scott Baldwin, R-Noblesville, SB 291 would expand the marshal service already protecting the Indiana Supreme Court justices and their staff to also the judges and staff of the Court of Appeals of Indiana and the Indiana Tax Court. These court marshals would preserve order in the courtrooms and the offices of the judges and staff, ensure the safety of the judges at public events, and maintain a security system at the Statehouse and at the private judicial residences.

The bill sailed through the Indiana Senate and was unanimously passed by the House Courts and Criminal Code Committee. It is scheduled for second reading in the full House on Monday.

However, during the committee hearing, Rep. Andrew Ireland, R-Indianapolis, asked about the scope of the personal information provision. That language was amended into the bill when the full Senate considered the measure and was offered in reaction to the Jan. 18 shooting that injured Tippecanoe County Superior Court Judge Steven Meyer and his wife at their Lafayette home.

The amendment, offered by Baldwin, covers all state and federal judges, current and retired, who reside in Indiana as well as their spouses and children who live in the same household. It prohibits information, such as a judge’s home address, cellphone number, email address, and driver’s license number, from being released to the public. Under the bill, anyone who publishes the information could be charged with a Class A misdemeanor, or, if the publication resulted in bodily injury, a Level 6 felony.

Ireland pointed out the list of protected personal information includes “election and campaign finance reports” and asked whether the entire report would be barred from the public. Indiana Supreme Court justices and judges of the Court of Appeals and Tax Court are not elected, but, rather, are appointed by the governor. Conversely, most trial court judges across the state do run in elections.

Baldwin told Ireland he intended for the provision to just remove the judges’ names and home addresses from the reports, but, he said, the language could possibly be clarified on second reading in the House.

Speaking to The Indiana Citizen after reviewing SB 291, Gerry Lanosga, associate professor of journalism at Indiana University Bloomington, said not disclosing home addresses and phone numbers of judges is common sense that even a “radical freedom-of-information person” would have difficulty opposing. He did, however, object to the prohibition on disclosing campaign finance reports, saying the public should be able to find out who is funding judicial campaigns and how those campaigns are spending that money.

“We run politics as a business and the influence of money, thanks to cases like (the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. FEC), is the coin of the realm,” Lanosga said. “This is how campaigns are run, this is how people seek and win office. (Since) that’s the case, I think it is in the interest of citizens to know who exactly is funding these political businesses and campaign finance disclosure laws are designed to make that possible.”

Lanosga was also concerned about the criminal penalties in the personal information provision in SB 291. He noted the Espionage Act of 1917 is one of very few pieces of legislation where any level of government has placed a ban on publishing information and even that federal law has raised questions about its constitutionality.

“I don’t know what responsible news organization, or even individual, is running around trying to publish judges’ personal information,” Lanosga said, “but the idea that the government is going to punish an individual or an organization for publishing information is definitely treading on territory that’s forbidden by the First Amendment.”

After the House committee hearing, Ireland called SB 291 “an important bill” and said he supported removing personal identifying information from public documents to help ensure the safety of judges.

“My point was the bill’s draft needs a small tweak to clarify that it does not mean campaign finance reports can be withheld from the public; any home addresses and other sensitive information can be removed if requested,” Ireland said in an email. “The author made clear that withholding campaign finance reports was not his intent with his bill and he is open to an amendment to fix that.”

Ireland did not indicate whether he was going to offer such an amendment. Also, Rep. Greg Steuerwald, R-Avon, one of the House sponsors of SB 291, did not respond to an email asking if he would try to tweak the language.

Baldwin told The Indiana Citizen he would support amending his bill to clear up the confusion. Then he went a step further and proposed deleting the personal information section altogether and relying, instead, on a similar provision in Senate Bill 140, which is seeking to curtail doxxing.

“As the bill moves forward in the legislative process, I will continue to work with my colleagues in the Senate and House to ensure Indiana’s judges can do their job without fear of intimidation,” Baldwin said in his email.

Authored by Republican Sens. Vaneta Becker of Evansville, Aaron Freeman of Indianapolis and Sue Glick of LaGrange, SB 140 was crafted in response to the threats and swatting several lawmakers encountered during the December fight over redrawing the state’s congressional districts. Like SB 291, the doxxing bill has strong bipartisan support and received a hearing but, so far, no vote by the House Courts and Criminal Code Committee.

SB 140 prohibits the posting of personal information with the intent to create fear or harm an individual. The bill defines “personal information” as including the individual’s name and residential address, Social Security number, and phone number. Also, the definition covers the name or address of the individual’s employer and the name or address of a place the individual frequently visits.

Lanosga noted the difficulty between protecting the right to privacy and the right of the public to know things. These are two ideals, he said, that are cherished in a democracy but clash quite often as part of the struggle to determine when an individual’s private actions become part of the public’s interest.

Referring to SB 291, Lanosga said campaign finance reports do not pose a threat to privacy. The public’s desire for “clean, non-corrupt politics” gives it a legitimate interest in following the money. And while the need to balance the public and private interests remains, he said, sometimes determining what is in the public’s interest is easy.

“I think, probably, most people can agree where that line is between a Social Security number, a cellphone number, and a $10,000 campaign contribution,” Lanosga said.

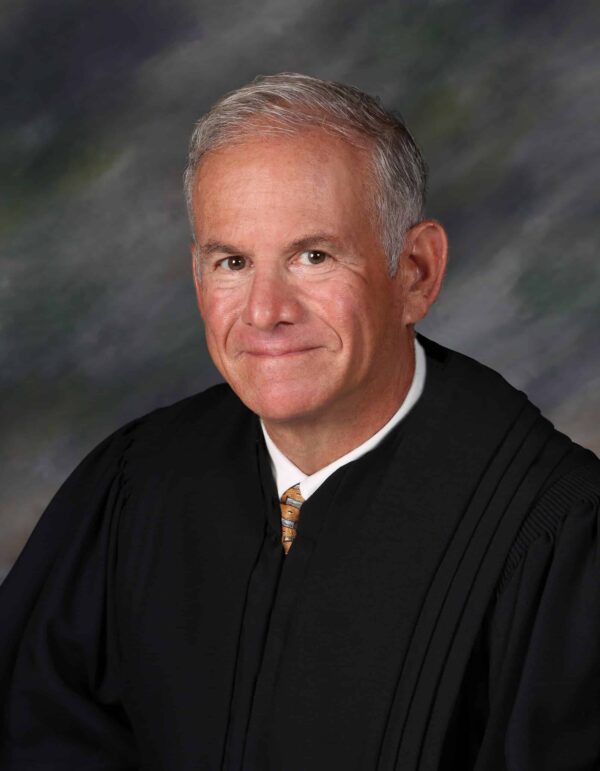

Indiana Supreme Court Justice Christopher Goff and Court of Appeals Judge Cale Bradford appeared at the House committing hearing on SB 291 and offered their support of the measure. Bradford said the bill was based on an existing statute in Maryland, but he did not specify the exact law and he did not make any comments about the personal information provision.

Lanosga questioned how the six defendants accused of plotting to kill Meyer, the Tippecanoe County judge, learned of his home address. He said they could have uncovered that information lots of ways – maybe even by following the judge home from the courthouse – and without knowing what happened, SB 291 might not be the right solution to the problem.

According to reporting by Based in Lafayette, court documents revealed that one of the defendants, Nevaeh Bell, confirmed Meyer’s address for the alleged shooter, Raylen Ferguson, by looking at an app that she used for her job.

Lanosga said SB 291 is trying to shield judges from dangers, but the inclusion of election and campaign finance reports on the list of undisclosable information could lead to a snowball effect with other public documents being subsequently blocked from public view.

“The public (has) to be able to have scrutiny and accountability over public officials,” Lanosga said, noting that if judges are exempted from revealing their campaign finance reports, lawmakers who have been threatened may push to be included in that exemption. “Pretty soon, we have a very secretive government that is difficult for citizens to really control.”

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org