By Marilyn Odendahl

The Indiana Citizen

January 20, 2026

The enthusiasm that sprouted in December for ending Indiana’s death penalty appears to have wilted for now, since a repeal bill offered last year was not reintroduced this legislative session and state lawmakers are, instead, considering legislation to expand the methods available for executions.

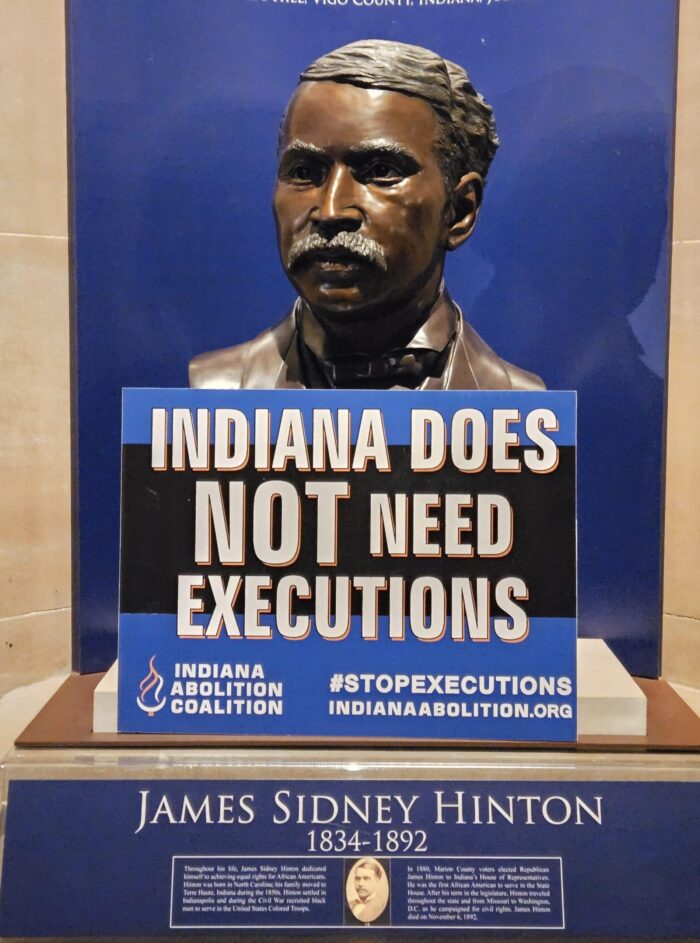

Indianapolis First Friends Quaker Meeting; Shalom Zone, an interfaith group; and the Indiana Abolition Coalition, a nonprofit trying to end the death penalty in the Hoosier State, were optimistic in December that the Indiana General Assembly might, at least, start a discussion on stopping capital punishment in the state. In particular, they were hopeful Rep. Bob Morris, R-Fort Wayne, would, again, file his bill to repeal Indiana’s death penalty.

However, last week, Morris issued a news release saying he had opted instead to introduce a bill that would require a team of legislators to oversee the executions carried out by the Indiana Department of Correction. He seemed to concede a full repeal of capital punishment was not possible at this time.

“I’m a pro-life legislator from conception until the final breath, and I do not believe that another human being should be taking a human life,” Morris said in the release. “But the reality is Indiana is a death penalty state. If lawmakers are going to advance and uphold laws that take a life, it’s those same lawmakers who should be responsible for committing the act. Don’t give anyone a job that you wouldn’t want to do yourself.”

Jodie English, criminal defense attorney and member of Indianapolis First Friends, speculated Morris is trying to bring transparency and accountability to the state’s executions by lethal injections. She said Indiana and Wyoming are the only states that do not allow the press to witness an execution, but Wyoming has not carried out a death sentence since 1992.

“I could intuit from that bill that he continues to be concerned about the secrecy,” English said of Morris’ legislation. “He wants personal responsibility.”

Morris’ proposed bill, House Bill 1287, would require the warden of the state prison to assemble an execution team from legislators who have volunteered to serve. The bill prohibits the death penalty from being carried out until the execution is fully staffed and the members are trained and certified in the DOC’s execution protocol.

His legislation also says the names of those legislators who volunteer for the team, or serve on it, would be a public record. However, there is no provision to allow a member of the media to witness an execution.

HB 1287 has been assigned to the House Committee on Courts and Criminal Code, but, so far, has not been scheduled for a hearing. For the bill to get any momentum this session, it will have to get through the committee and to a third reading before the full House by Jan. 29.

Two new bills that have gained traction would give the state more options to go forward with an execution if the drugs are not available for a lethal injection or if the alternative method is requested by the condemned individual. Senate Bill 11, authored by Sen. Mike Young, R-Indianapolis, would allow the death penalty to be carried out by firing squad, while House Bill 1119, authored by Rep. Jim Lucas, R-Seymour, would allow a firing squad or nitrogen hypoxia to be used in an execution.

Young’s bill was heard by the Senate Corrections and Criminal Law Committee on Jan. 6, where it is still awaiting a committee vote. Lucas’ bill is on the House Courts and Criminal Code Committee’s Jan. 21 meeting agenda.

First Friends and Shalome Zone were encouraged by Molly Craft, Braun’s chief of staff for communications, to shift their strategy from repeal to asking legislators to conduct a study of the death penalty, English asid. That suggestion has drawn little support, she said, with First Friends holding to its stance that it cannot support any kind of purposeful killing.

Still, English believes the expansion bills are actually a sign that support for the death penalty is eroding in Indiana. She said the bills are a way of “changing the music,” because they focus on providing an alternative to the costs and availability of the lethal-injection drugs and leap over the policy priorities and moral issues of capital punishment.

“I think it’s a way of ducking the question,” English said.

The battle at the Statehouse between opponents and supporters of the death penalty comes as more than 50 organizations, including the Indiana Abolition Coalition, have recently launched the U.S. Campaign to End the Death Penalty. This national effort to stop capital punishment is focused on providing expertise and resources to help local groups in their opposition work.

“We see a very clear disconnect between the handful of politicians pushing for more executions and the expansion of the death penalty and current public sentiment on this issue,” Laura Porter, executive director of the U.S. Campaign, said at the launch of the initiative in December. “We want to make sure policy makers know the country is moving away from the death penalty. The surge in executions and efforts to expand the death penalty are out of touch with the view of Americans.”

Porter pointed to statistics that show declining public support for the death penalty. An October 2025 Gallup Poll found a slim majority of 52% of Americans were in favor of the capital punishment for individuals convicted of murder, a marked drop from the all-time high of 80% in September 1994. A December 2025 report by the Death Penalty Information Center noted only 23 death sentences had been handed down in 2025, the fifth year in a row that fewer than 30 people were sentenced to death in a single year.

Sarah Craft, interim director of the Indiana Abolition Coalition, said Hoosier juries were also moving away from sentencing criminal defendants to death. According to information on the Indiana Public Defender Council’s website, the last person given the death penalty in the state was William Clyde Gibson III in 2014. Three individuals are currently defendants in capital cases but one, Carl Boards II, has been found incompetent to stand trial, while two others, Orlando Mitchell and Dalonny Rodgers, have their trials scheduled for later this year.

Craft said Indiana’s executions in 2024 and 2025 have brought capital punishment back into public consciousness and led to a willingness to examine the implications of executions. Even so, she noted that ending the death penalty in the state will likely take several more years and require bipartisan support.

“I think we’ve seen in other states around the country that this is a multi-year conversation that requires some intent and partnership with lawmakers,” Craft said. “Once those lawmakers sort of see both the dwindling support for the death penalty as well as the truth about the flaws in the death penalty that they will choose to sort of give up on the failed experiment.”

The Indiana Abolition Coalition is active this legislative session, despite the repeal bill not being filed. Craft testified against Young’s firing squad bill during the committee hearing and released a statement afterward, saying Indiana is continuing to waste “millions of dollars on a punishment that is arbitrary, doesn’t deliver public safety, and threatens innocent lives.”

Opponents of the death penalty cite to practical and moral reasons for ending capital punishment. The Death Penalty Information Center noted capital cases cost a lot more for taxpayers and take years to wind through the courts, have been shown to be biased against minorities, and have ended with innocent people being wrongly convicted.

Demetrius Minor, executive director of Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, which is part of the U.S. Campaign, said Rep. Morris’ repeal bill is part of a trend emerging in other states. Capital punishment is falling out of favor with Republicans and conservatives, because it does not align with their pro-life and small-government values.

Craft also noted that guards and other prison workers suffer emotional and mental-health issues at the penitentiaries where the executions are conducted. Moreover, she said, victims’ families suffer, too, because they are offered little support during the criminal trial and extensive appeals process in the death-penalty cases.

“One thing that I’ve learned in my more than 20 years doing this work is how much the death penalty fails victims’ family members,” Craft said. “I just don’t think that we hear that story enough. … There are not enough resources for families of homicide victims, those resources are, in many ways, inaccessible to people, and the decades of appeals and return to court and having the people who committed these crimes in the spotlight has been horrific on these folks.”

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org.