By Marilyn Odendahl

The Indiana Citizen

January 2, 2026

The state of Indiana asked a federal district court on Monday for a reprieve from an injunction issued more than two decades ago, so an 11,500-pound limestone monument that includes an inscription of the Ten Commandments can be installed on Statehouse grounds.

Indiana asserts in its brief supporting its motion for relief that the precedent used to block the monument from being displayed on the Statehouse lawn has since been overturned by other rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court. The state contends a majority of the justices have since rejected the view that the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution prohibits displays of the Ten Commandments on public property and, according to the brief, have adopted a new standard that requires the courts to determine whether such a religious monument reflects the history and tradition of the United States.

“Placing the Monument on the Statehouse grounds would be consistent with the established practice of recognizing formative legal documents, including the Ten Commandments, at the Statehouse,” the state’s brief, filed in the Southern Indiana District Court, argues.

However, Americans United for Separation of Church and State disputed Indiana’s interpretation of court rulings and said the renewed push for the Ten Commandments monument is being fueled by Christian nationalists.

“Trying to resurrect a Ten Commandments display at the seat of Indiana’s government is textbook Christian nationalism,” Andrew L. Seidel, constitutional attorney and vice president of strategic communications for Americans United, said in an email. “This move shows a lack of respect for Hoosiers’ religious freedom, the rule of law, and our Constitution’s promise of church-state separation.”

Indiana’s motion comes more than 20 years after a split 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s injunction in 2001 and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2002.

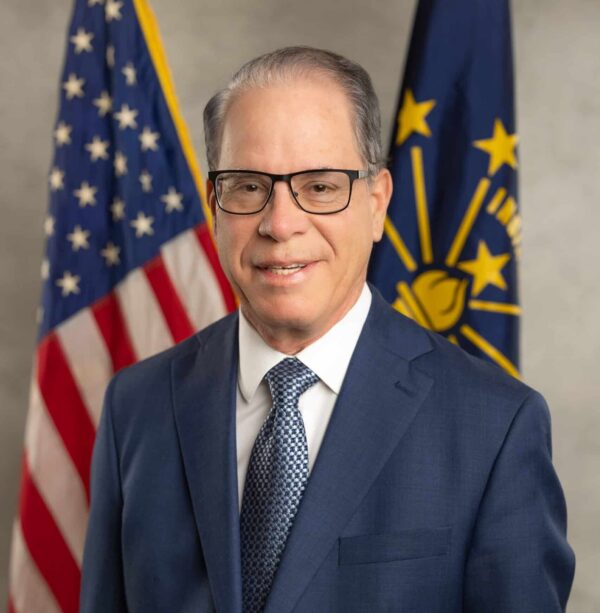

In a joined statement, Indiana Gov. Mike Braun and Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita called the marker a “historical monument” and said it was similar to another display of the Ten Commandments that stood on the Statehouse lawn for more than 30 years before it was vandalized in 1991.

According to the state’s brief, Braun, a Republican, decided the monument, which is currently in Bedford, should be relocated to the Statehouse grounds and placed among the other monuments, markers and displays.

“The monument reflects foundational texts that have shaped our Nation’s laws, liberties, and civic life for generations,” Gov. Mike Braun said in a press release. “Given the clear shift in constitutional law and the long history of similar displays across the country, we ask the court to lift this outdated injunction. Restoring this historical monument is about honoring our heritage and who we are as Hoosiers.”

Americans United said the monument was not only religious in nature but also elevated one faith above all others.

“The Indiana Statehouse and the public officials who work there should welcome people of all religions and none,” Seidel said. “Displaying a Ten Commandments monument does the opposite; it sends a message to all Hoosiers that one faith is favored over others, especially when placed alongside the Bill of Rights.”

The fight over the monument actually took place when the late Frank O’Bannon, a Democrat, served as governor. He accepted the monument as a gift from the Indiana Limestone Institute in 2000 and announced plans to place it outside the Statehouse.

Nodding to the previous Ten Commandments monument that stood on the state capitol’s grounds, O’Bannon said the former monument “stood on the Statehouse lawn as a reminder of some of our nation’s core values” and added that the new monument would be an “integral part of the Statehouse setting, which honors the history of our state and our nation.”

The monument is a 4-foot, 4-inch tall block of limestone that sits atop a larger rectangular base also made of limestone. The Ten Commandments are inscribed on one side of the block and the Bill of Rights are etched on the opposite side. Smaller sides of the block contain the preamble to the 1851 Indiana Constitution and a dedication showing the monument was a gift from the Indiana limestone industry.

In May 2000, the Indiana Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit, saying the monument’s placement on the Statehouse lawn would constitute an unlawful establishment of religion.

The Southern Indiana District Court agreed. In its ruling, the court applied the so-called Lemon test, which was crafted by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman opinion and used to determine when a government entity was violating the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause by promoting one religion above all others.

The district court found the Indiana case, Indiana Civil Liberties Union et al. v, O’Bannon, 1:00-cv-00811, failed two parts of the Lemon test. Notably, the court ruled the state’s purpose in erecting the monument was for religious, not secular, reasons. Also, the court held the Ten Commandments were so prominently displayed that a “reasonable person” could infer that the state government was showing a preference for one specific religion.

As part of its brief, Indiana argues that in rulings issued since O’Bannon, the U.S. Supreme Court has “discarded the Lemon test.” The state cites to the 2022 decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, where the Supreme Court found a high school could not prohibit the football coach from praying on the 50-yard line after games and, pointing to 2014’s Town of Greece v. Galloway, held “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’”

Also, Indiana’s brief notes that in Van Orden v. Perry from 2005, the Supreme Court observed the “role played by the Ten Commandments in our Nation’s heritage” and that the commandments were displayed at many government buildings in Washington, D.C., including the U.S. Capitol, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the U.S. Department of Justice and even in the U.S. Supreme Court’s own building.

Quoting from the dissent in the 7th Circuit’s opinion in O’Bannon, the state asserts in its brief, “The Ten Commandments’ inclusion on Indiana’s Monument is ‘merely an acknowledgement of the historical fact that the Ten Commandments served as an integral part of the foundation for our country’s legal system.’”

Indiana is asking the district court to allow the installation of the monument, saying the “injunction improperly dictates which monuments the Governor may place on Statehouse grounds.”

Attorney General Rokita did not mention the Ten Commandments in his statement supporting the placement of the monument on state property, but said the “historical recognition” was part of Hoosiers’ “common story.”

“The Statehouse grounds feature many monuments and markers celebrating Indiana’s and America’s heritage,” Rokita said in the press release. “This monument belongs among them as a reminder of core principles that have guided our nation.”

The plaintiffs have 14 days to respond to Indiana’s motion.

Ken Falk, legal director of the ACLU of Indiana, represented the plaintiffs in O’Bannon. In a statement to The Indiana Citizen, he indicated they rejected the state’s position.

“We are aware of this filing,” Falk said of Indiana’s motion. “We don’t think it’s appropriate and we will be opposing it.”

Dwight Adams, an editor and writer based in Indianapolis, edited this article. He is a former content editor, copy editor and digital producer at The Indianapolis Star and IndyStar.com, and worked as a planner for other newspapers, including the Louisville Courier Journal.

The Indiana Citizen is a nonpartisan, nonprofit platform dedicated to increasing the number of informed and engaged Hoosier citizens. We are operated by the Indiana Citizen Education Foundation, Inc., a 501(c)(3) public charity. For questions about the story, contact Marilyn Odendahl at marilyn.odendahl@indianacitizen.org.