July 1, 2021

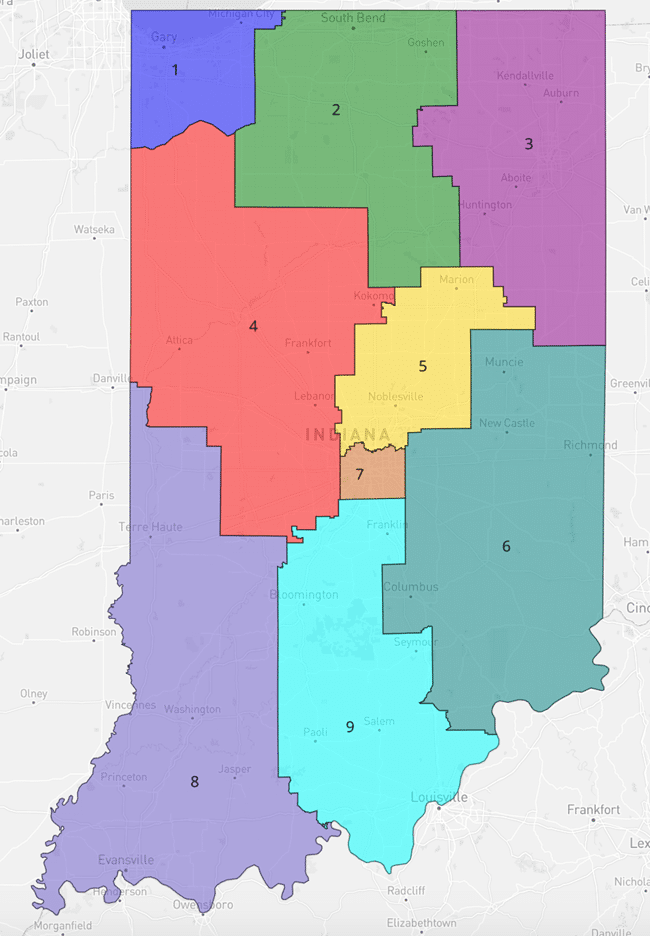

A new study says Indiana’s 2011 redistricting disproportionately favors Republicans over Democrats, creating unequal representation that is “bad for democracy,” a claim state Republicans deny.

Women4Change, a nonpartisan organization, hired Christopher Warshaw of George Washington University to analyze 50 years of Indiana’s voting data against the 2011 legislative and congressional maps.

His conclusions, as summarized at the end of the report:

• “Indiana’s 2011 districting plan had a very large pro-Republican bias. Based on a variety of metrics, the pro-Republican bias in Indiana’s congressional and state legislative districting plans is extremely large relative to other states.

• “The pro-Republican bias in Indiana’s plan cannot solely be a function of geography: Based on a variety of metrics, Indiana’s congressional and state legislative plans are much more pro-Republican than prior to the 2011 redistricting. Thus, the current Efficiency Gap in Indiana cannot solely be a product of geography.

• “The pro-Republican advantage in congressional and state legislative elections in Indiana causes Democratic voters whose votes are wasted to be effectively shut out of the political process in Congress. Due to the growing polarization in Congress, there is a large difference between the roll call voting behavior of Democrats and Republicans. In today’s Congress, a representative from one party increasingly does not represent the views of a constituent of the opposite party. Thus, Democratic voters whose votes are wasted are unlikely to see their preferences represented by policymakers.”

Among the metrics used in Warshaw’s analysis, according to an executive summary of the report, is “the Efficiency Gap, which flags the effects of ‘packing and cracking”’ — concentrating or fragmenting opposition party voters for political purposes –“by comparing mathematically how efficiently each party converts its votes to seats. In a gerrymandered map, one party’s votes will yield legislative seats much more efficiently than the other’s.”

Rima Shahid, executive director of Women4Change, said the organization commissioned the study in hopes that it would provide insight as the 2021 redistricting approaches.

The way districts are currently drawn “gives the controlling [Republican] party a disproportionate legislative supermajority that can ignore any input from the minority party [and] as a result, new laws make no allowance for the wishes of one party’s vote,” Shahid said.

“So it’s one party that’s really able to control the bills and the number of bills that pass through and then essentially become laws. We have an overwhelming supermajority.”

The study has drawn criticism from the Indiana Republicans.

“Indiana’s legislative maps are some of the most fairly drawn in the entire country,” Indiana Republican Party Chairman Kyle Hupfer said in a statement to The Statehouse File. “For years, the Democrat party has used unsubstantiated claims of gerrymandering to deflect from the fact that Hoosiers have rejected Democrat candidates at the ballot box year after year.

“For nearly two decades, Hoosiers have trusted Republican leadership from the courthouse to the Statehouse. Indiana Republicans hold every statewide elected office in Indiana, supermajorities in both houses of the General Assembly, both U.S. Senate seats, 71 mayoral offices and 88% of all county elected positions. The sustained success of our party is due to our policies, our candidates, our volunteers and the support we’ve earned in every corner of the state.”

As of today, in the Indiana House of Representatives, there are 29 Democrats and 71 Republicans, while in the Senate, there are 11 Democrats and 39 Republicans.

Redistricting occurs every 10 years after the U.S. Census is completed and published. However, due to COVID-19, the results were delayed, pushing back the process in Indiana and other states.

Warshaw, the study author, said he was surprised by what he characterized as extreme partisan bias.

Warshaw said that on average, Democrats get up to 45% to 55% of the votes but only 22% of the legislative seats. He said that it does not make sense that the Republican party has around 60% of the votes but ends with 80% of the Senate seats, for example.

“The problem with gerrymandering is that, if one party has a lock on power, no matter how many votes they get, that’s bad for democracy, [It] means they don’t have to be responsive to what the public wants; it means they can do undemocratic things,” Warshaw said.

Senate President Pro Tem Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, promised a transparent and fair process in 2021.

“In Indiana, the General Assembly is responsible—per our state’s constitution—to draw legislative and congressional maps, and that’s a task we take very seriously. Public trust in the process is paramount, and to that end, we intend to have a very transparent process where we gather feedback from Hoosiers across the state,” Bray said in a statement to The Statehouse File.

“Drawing legislative maps that are fair is my top priority as we approach redistricting, and we hope to soon have the data needed to formally begin the process.”

Jay Yeager, an Indianapolis lawyer for voters in recent gerrymandering litigation and a volunteer with Women4Change, said that the gerrymandering in Indiana did not happen by accident and that the members involved were aware of their actions.

“Think about what a gerrymander does, it really attacks the voters of one party and penalizes them for being members of that party, for having those political views, because it packs them into a few districts,” Yeager said, “so that there they waste a lot of votes and they can’t elect very many representatives, and hence we have these super majorities.

“The Democrats are very grossly underrepresented. They don’t have any influence, and the Republicans do whatever they want to do, and I don’t think that’s healthy.

“I don’t think it’s healthy for the state in the long run for 40% to 45% of its citizens to feel they have no input in their government, that our government ignores them because the other party’s in charge. That’s kind of un-American.”

Warshaw said that one of the solutions would be having a nonpartisan commission in charge of drawing the district lines. According to Ballotpedia, seven states, among them Arizona, California, Michigan and Washington, utilize such commissions.

Warshaw says that public awareness is what’s going to get the state back into a fair and equal distribution of political power and representation.

“Because at the end of the day,” Warshaw said, “in a democracy, a crucial part of the puzzle is just citizens being engaged by holding our elected officials accountable for doing things that are either bad policies or, in this case, sort of violate democratic norms.”

Shahid encourages citizens to continue to learn about redistricting and keep their lawmakers in check.

“You have to care about redistricting because, ultimately, the folks that get to author and vote on laws are the ones that are drawing these maps. And so if we want to see change in terms of legislation, the first process is making sure that we are engaged and shed a light on the redistricting process,” Shahid said.

“We owe it to our next generation to make sure that Indiana continues to be a place that attracts and retains great people.”

Carolina Puga Mendoza is a reporter for TheStatehouseFile.com, a news website powered by Franklin College journalism students.