Continuing our coverage of this year’s redistricting process, the following report was written by Indiana journalist Janet Williams for The Indiana Citizen.

May 14, 2021

The passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 2015 presented Indiana with an interesting question: Did the actions of its state legislature really reflect the will of the governed?

What came next suggested they did not.

Only a few weeks after its enactment by an overwhelming margin, an outcry from business and tourism interests — eventually reinforced by polling of the public at large — forced a legislative “fix” that quickly and plainly undid much of the new law.

As the Indiana General Assembly prepares to redraw congressional and legislative district lines later this year, the lessons of RFRA remain, showing how policy can be shaped when a single party controls almost all the power in a legislative body.

“RFRA never would have happened without so many conservative legislators being entrenched in uncompetitive districts,” said Julia Vaughn, policy director for Common Cause Indiana. “I think RFRA is really the thing that caused so many Hoosiers to recognize for the first time that gerrymandering has happened in our state, and boy, it really matters.”

While gerrymandering — or in its less manipulative connotation, redistricting — may sound like it’s a game played by powerbrokers, its results have real-life implications for the lives of Hoosiers. A decade of single-party control has resulted in a legislature more conservative and more rural than the public it represents and prone to passing laws that can run counter to the wishes of an increasingly metropolitan population.

During the same decade, voter turnout – a key measure of any state’s civic health – has continued to fall in Indiana in relation to that in other states. Despite a sharp increase in the 2020 general election, the state ranked only 43rd when compared to the rest of the nation.

Mike Schmuhl, the new chair of the Indiana Democratic Party, said that since so many districts are tilted heavily Republican, many voters won’t even bother going to the polls.

“That is really harmful to any democracy where people sort of shrug their shoulder and say my vote doesn’t count, doesn’t make a difference,” Schmuhl said. “And that’s incredibly unhealthy for any representative democracy.”

***

Gerrymandering is defined as the manipulation of political boundaries to favor one constituency over another. The term comes from a Massachusetts legislative district drawn in 1812 to favor the political party of Gov. Elbridge Gerry; it resembled a salamander.

Whether Indiana is gerrymandered depends to some degree on how the constituencies are defined.

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that legislative districts cannot be gerrymandered to marginalize people in minority communities.

But marginalizing people because of their political party is another matter, according to a separate ruling in 2019, stemming from a redistricting in North Carolina that was challenged by Democrats on the grounds that it marginalized their voices in the state’s congressional map; Republicans in Maryland had filed a similar challenge making the same claim against Democrats in the majority there.

In Rucho v. Common Cause, the high court ruled that gerrymandering is a political issue which should be addressed at the state level — and not by federal courts.

So when considering only what is not allowed constitutionally, such as marginalizing voters because of race, then an argument can be made that Indiana is not gerrymandered.

“However, if you look at it from the perspective of party competition,’’ said Andrew Downs, an associate professor at Purdue University-Fort Wayne and director of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics, “then you could begin to make an argument that it is.”

The laws governing how legislative district maps are drawn are more straight-forward.

Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution requires a count of people living in the United States once every 10 years. Those numbers are then used to determine how many seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are allocated to each state.

In Indiana, the General Assembly is responsible for drawing the state legislative as well as congressional district maps, and the only requirement is that the borders must be contiguous or unbroken. By that standard, Indiana’s legislative maps conform to the law.

But are voters choosing their lawmakers or is it the other way around?

Sheila Kennedy, professor emeritus in the Paul H. O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, has written about gerrymandering. She points to a University of Chicago study that ranks Indiana among the most gerrymandered states in the country based on the number of “wasted votes’’ — the votes of the minority party that don’t really count because a district is so overwhelmingly Republican or Democratic.

“The districts, maybe they’re square, but do they respect communities? Do they respect communities of interest? Do they respect community boundaries?” she asked. “Actually, you could draw a great big square in the middle of Indiana and take in a whole lot of people whose basic concerns are very, very different.”

One example is Indiana Senate District 28, which extends like a middle finger from heavily Republican Hancock County into a relatively small portion of heavily Democratic Marion County, taking in the Indianapolis community of Irvington. The issues affecting mostly rural Hancock have little in common with the urban neighborhood.

That is why state funding for projects such as road maintenance often shortchanges urban areas, Kennedy said, because the money is allocated based on the number of miles of roads – greater in rural counties — and not on the amount of traffic, which is greater in and around cities like Indianapolis.

According to 2018 population estimates, 72% of Hoosiers – but only 56% of their legislators — live in a metropolitan area, which includes cities and immediate suburban areas.

“That plays itself out on a lot of issues, for example, guns, mass transit,” said Vaughn of Common Cause. “Rural Indiana and urban Indiana are pretty different places. And I think the voters in those places have different needs.”

***

How the Indiana General Assembly came to be dominated by one party can be traced to the legislative redistricting process in 2011, when Republicans secured control of the House in addition to the Senate and the governor’s office.

As a result, two congressional districts — the Second in northern Indiana and the Ninth to the south — went from being competitive in most elections to strongly Republican. The Indiana House, which had flipped from Republican to Democratic control and back during the previous two decades, became solidly Republican, relegating Democrats to a super-minority status that continues.

Republicans hold two supermajorities — 71-to-29 in the House and 39-to-11 in the Senate — which mean that they can conduct business and enact laws without any input from Democrats. In Congress, Republicans hold seven of Indiana’s nine seats.

Rodric Bray, the Indiana Senate’s top Republican and a key player in this year’s redistricting process, says that rather than the result of gerrymandering, those numbers are a reflection of Republican strength at the grassroots, pointing to the 9-to-1 advantage that the party holds in elected county offices throughout the state.

The most full-throated defense of Indiana’s 2011 maps might have come earlier this year in an Indianapolis Star op-ed by Pete Seat, a former White House spokesman for President George W. Bush and campaign spokesman for former Director of National Intelligence and U.S. Senator Dan Coats.

“To be sure,’’ Seat wrote, “examples of gerrymandering, where politicians draw oddly shaped district boundaries to maintain or gain political power, are found in many states, with particularly ugly examples in Maryland, Texas and Illinois. But they aren’t found in Indiana. Here, gerrymandering is not in the eye of the beholder, but in the eye of the loser.’’

But is Indiana really as conservative as the numbers indicate? Vote totals in congressional elections tell a different story.

Overall, Democrats got about 40% of all votes cast in the 2020 congressional races in Indiana. That would translate to three or four seats in Congress rather than the two that Democrats now hold.

“That’s the concept of proportional representation, that your division of seats in your legislature should at least somewhat resemble what the vote totals boiled down to be,” Vaughn said. “Certainly, in Indiana we don’t have anything that looks like proportional representation and I think the only way to explain it is that districts were drawn to favor one party over the other.”

Another factor that suggests gerrymandering is the number of seats won with a margin of 60% or greater — 32 Republican and four Democratic seats in the House, eight Republican and three Democratic seats in the Senate. And in 39 other legislative districts — 20 held by Republicans and 10 by Democrats in the House, three held by Republicans and six by Democrats in the Senate — the opposing party didn’t even field a candidate.

“If you’re looking for why there is not more competition, I think that you absolutely can say the lack of the prospect of winning keeps people from running,” said Downs, the political science professor in Fort Wayne. “I mean why would someone want to run in a race, where the previous person lost 60-40 or 70-30.”

***

In the decade since the last redistricting in Indiana, groups such as Common Cause and the League of Women Voters have pushed for legislation to create an independent commission to draw legislative districts, but the efforts died quickly in the General Assembly.

Legislation further restricting abortion and easing controls on gun ownership, along with religious freedom bills like RFRA, advanced. An often-introduced bill to allow “constitutional carry’’ – repealing Indiana’s requirement of a permit to carry a handgun – made unprecedented progress in the 2021 legislative session, passing the House by more than a 2-to-1 margin but dying in the Senate.

Downs says Republicans actually might have shown restraint in exploiting their supermajorities.

“When you consider the fact that the legislature has been in the supermajority control of the Republicans for, let’s just call it 10 years right now, they could have done an awful lot more and that’s cold comfort to some folks,” Downs said. “But if the maps are drawn in a way that helps to solidify Republican control at the high majority or supermajority level, then that will enable them to move faster in the direction of more conservative policies.”

The question is whether those more conservative policies reflect the views of most Hoosiers.

The original RFRA legislation, which could have allowed businesses to deny services to people in the LGBTQ community because of religious beliefs, passed the Indiana House by a 63-to-31 margin and the Senate 40-to-10.

However, a survey conducted in 2015 by Ball State University’s Bowen Center for Public Affairs showed that 52% of Hoosiers said they believed that a business providing wedding services to same sex couples, for example, should be required to provide the same services to all. The same survey also found that 57% of Hoosiers supported amending the state’s civil rights laws to provide protections for sexual orientation and gender identity.

***

Beyond Indiana, the 2011 redistricting process was a turning point as well.

In 2010, the national Republican State Leadership Committee funded an effort called REDMAP, short for Redistricting Majority Project, to win majorities in state legislatures in order to control the redistricting process in 2011.

They were largely successful as Republican-held legislatures had unilateral power to draw 193 congressional districts while Democratic-held legislatures accounted for 44, according to David Daley, author of Rat F**ked, Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count.

The results soon became apparent. In the book, Daley noted that even though Democrats running for Congress in 2012 received 1.4 million more votes than Republicans nationally, Republicans kept a 33-seat majority.

Peter Miller, a researcher at the Brennan Center for Justice, points to Wisconsin as a state where Democrats were locked into a permanent minority status in the last decade even when they won more votes overall than Republicans. Wisconsin was one of the states targeted by REDMAP.

With a new majority, Republicans in the legislature and governor’s office in Wisconsin stripped public sector unions of the right to collective bargaining in 2011. Massive protests at the capitol in Madison had no impact on the outcome.

“You can rely upon the sort of REDMAP-type tactics that Dave Daley discusses in his book as a means to assure that more of your team is in the legislature, and once you accomplish that objective then you can pass whatever policies, you would like,” Miller said.

Both parties are guilty of gerrymandering legislative districts to hold onto political power, but “the good news though is that the states that have departed from legislative redistricting tend to have more fair outcomes that have conditions, tend to do a better job,” Miller said.

Citizens in Ohio and Michigan will have a chance to see whether independent commissions do a better job of redistricting. Voters in both states approved ballot initiatives to change the process from 2011, when state legislatures were in control.

***

Indiana doesn’t have a process for ballot initiatives.

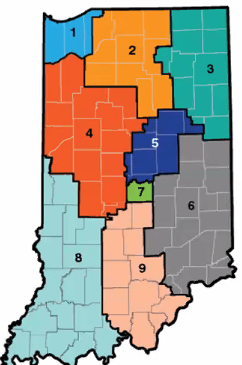

Instead, Common Cause Indiana is leading an effort to invite citizens to use census data and draw legislative districts based on criteria they believe is important, such as communities of interest and creating more competitive races. The independent Indiana Citizens Redistricting Commission has been meeting virtually with voters in each of the nine congressional districts to understand what they believe should be considered as new legislative maps are drawn and will be given a chance to draw their own maps.

The hope is to show lawmakers that the process can be transparent and fair.

“I think we’re just in the midst of a national debate over, who we want to be in charge of this process and the compelling argument, at least from my perspective is, we should probably do what we can to reduce conflicts of interest in policymaking,” Miller said.

It’s a conflict of interest for lawmakers to be drawing their own districts and it’s apparent to everyone except the lawmakers themselves, he said, adding, “In a sense that you can manipulate the election such that you’re pretty sure that your team is going to win, is it really an exercise that expresses the consent of the governed?”

Janet Williams recently retired as executive editor of TheStatehouseFile.com at Franklin College. She formerly worked in corporate communications for Cummins Inc., and as a reporter and editor at The Indianapolis Star.