Although the discussion was respectful and polite during a Tuesday evening forum, four Democratic candidates for Indianapolis mayor nevertheless offered very different views of the city and its future.

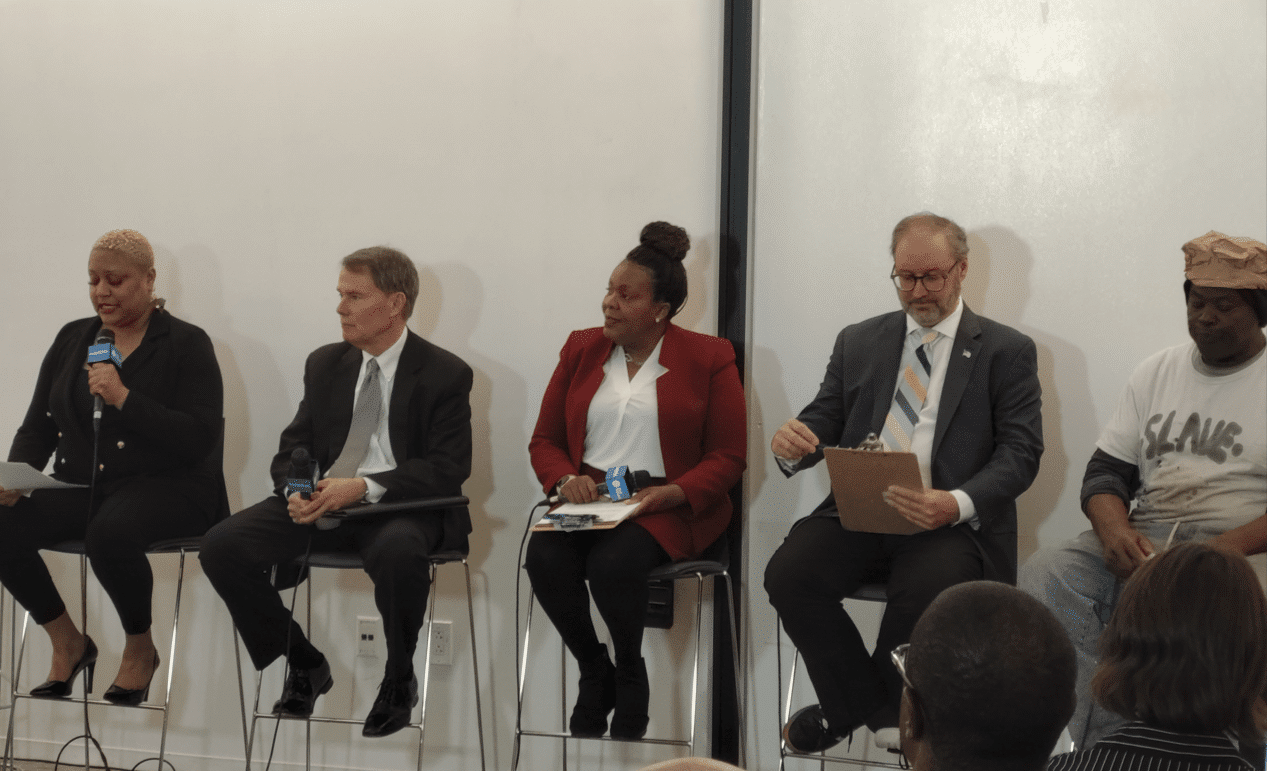

The mayoral town hall, hosted by The Indianapolis Star, brought Mayor Joe Hogsett (above, second from left) and three primary challengers – state Rep. Robin Shackleford (above, center); community activist Clif Marsiglio (above, second from right); and businessman Larry Vaughn (above, right) – together to answer questions from the voters; Bob Kern, a perennial candidate for office for the past 25 years, is also on the Democratic ballot. Oseye Boyd (above, left), public engagement editor at The Star, moderated the hour-and-a-half discussion that was presented to a live audience of about 80 people and broadcast on YouTube and Facebook.

An audience comprised of people of different ages and races listened attentively, never shouting, talking back to the candidates or applauding. Likewise, none of the candidates interrupted or argued with each other but silently listened while their opponents spoke and, in some instances, nodded in agreement.

Hogsett emphasized the third term he is seeking will be his last. The COVID-19 global pandemic caused “three of the most difficult years in our city’s history,” he said, and disrupted the “momentum we had created in the first term.” He wants another four years in office to finish the job he started in 2015.

“It has been an honor to represent Indianapolis and this city,” Hogsett said. “…I’m excited for the next four or five years for our city. I think we’ve got a lot to look forward to.”

However, his opponents pointed to the city’s struggles with gun violence and crumbling streets as evidence Indianapolis needs a change in leadership. They offered solutions that ranged from revamping the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department to potentially raising taxes to fix the potholes to a complete hands-off approach toward public safety.

Crime

In response to the first question about what big risk would they undertake as mayor, Marsiglio immediately cited the need to take a new approach to combat crime. He talked about restructuring the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department to divert 200 officers to be “unarmed civilian respondents” to handle situations involving mental health and substance abuse issues.

“We need to reinvest, we need to re-envision what we believe in as public safety,” Marsiglio said later in the discussion. “And, it’s, again, it’s not just the police.”

Hogsett defended his record, saying Indianapolis has been recording a rise in gun violence for the past 20 years. Then the pandemic added to the increase. His administration, he said, has responded by appropriating $150 million to preventing gun violence plus another $30 million to address mental health issues in the community. Also, he highlighted the mobile crisis assistance teams and the partnership with Faith in Indiana to have mental health professionals responding to situations where substance abuse or mental health may be an issue.

He said the investments “are starting to have positive effects. … Last year alone, 2022, we saw the largest single decline in murders in the history of the IMPD. Not declared victory but the progress is being made.”

Still, Shackleford noted the widespread fear of crime. She cited a survey she sent as a legislator to her constituents in which 60% of the respondents said they did not feel safe in their neighborhoods.

She said as mayor she would bring back the position of public safety director because the community needs someone at the administrative level who can handle law enforcement issues. Indianapolis is too big, she added, for the mayor to oversee public safety and run the city.

For accountability and transparency, she would require the body camera footage from any police involved shooting be available to the public within 48 hours of the incident. Officers who turn off their body camera would face a monetary fine and, under state law enacted in 2021, a misdemeanor charge. Also, to prevent crime, she wants the city to partner with schools and faith-based as well as community-based organizations to provide a safe place for youths and teach them how to resolve disputes without picking up a gun.

“When I am mayor, public safety will be my top priority,” Shackleford said. “… My goal is to focus on root causes of crime; rebuild the IMPD and right-size our force to our needs; restore trust and accountability between the community and law; and secure our families against gun violence.”

Vaughn advocated for giving the police commissioner and the Fraternal Order of Police complete control over the money appropriated to law enforcement and letting them run the IMPD as they want. He does not believe the mayor should have a role in public safety.

“If somebody’s going to murder, they’re going to do it,” Vaughn said. “I don’t think that should even be something that the mayor is actually concerned about.”

Potholes

The candidates agreed on two things about the local infrastructure – Indianapolis’ streets are in great disrepair and the formula used by the state to appropriate money for roads is woefully underfunding Marion County.

Shackleford hammered on the conditions of the city streets, calling the number of potholes a crisis and saying motorists driving around the city are damaging their cars. To get more money to fix the roads, she would use her experience in the Indiana General Assembly and the relationships she has built to “figure out how are we going to fund Marion County roads.” She vowed she is “not going to stop until we get this done.

Also, the state representative said people have indicated they are “willing to pay a little bit more” to have better roads. “I don’t know what that ‘little bit more’ looks like but that’s maybe an option,” Shackleford said. “I’m going to say all options are on the table because we have gotten to the point where it’s so bad because we have not sat down and taken risks, and sat down and collaborated and gotten solutions that now we’re in crisis mode.”

Hogsett immediately countered he was not going to ask Marion County taxpayers to pay more taxes than they already do.

“We are a donor county,” Hogsett said. “We pay into state government much more than Marion County receives and I’m not going to ask Marion County taxpayers to foot any of the roads bill.”

He highlighted the $1.1 billion infrastructure investment the city county council recently authorized to fund improvements over the next couple of years in the city. But, like Shackleford and Marsiglio, he faulted the state funding mechanism which pays a flat rate to counties for roads. This calculates into a a one lane mile road in a rural part of the state being appropriated as much money as the multiple-lane Keystone Avenue gets in Indianapolis.

“That has to stop,” Hogsett said.

Marsiglio seemed to favor a commuter tax. He talked about the communities surrounding Indianapolis and said the doughnut counties have to pay their fair share.

“One of the problems we have with this is we have the wrong messaging when we say that and anybody listening out in the audience from those doughnut counties, yeah, I want you to pay,” Marsiglio said. “And we should be a little bit nicer about how we say it.”

Vaughn said, “our roads are in shambles” and linked the disrepair of the roads, in part, to the number of heavy trucks that are traveling local thoroughfares because of the multiple construction projects. His solution mirrored his plan for public safety in that he would appoint a commissioner who would receive the road money and determine how to spend it. — Marilyn Odendahl