By Marilyn Odendahl

The Indiana Citizen

June 9, 2023

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita’s battle to keep private a report about his attempt to moonlight while holding public office is taking a breather as his attorneys from The Bopp Law Firm tend to their own legal matters including litigation over the state’s political contribution law and unpaid legal bills.

The attorney general’s office hired the Bopp firm in April 2023 to provide help with civil legal work. The first case the firm was assigned was the dispute over an advisory opinion from the Indiana Office of the Inspector General about the job Rokita retained with Apex Benefits after he became the state’s top lawyer.

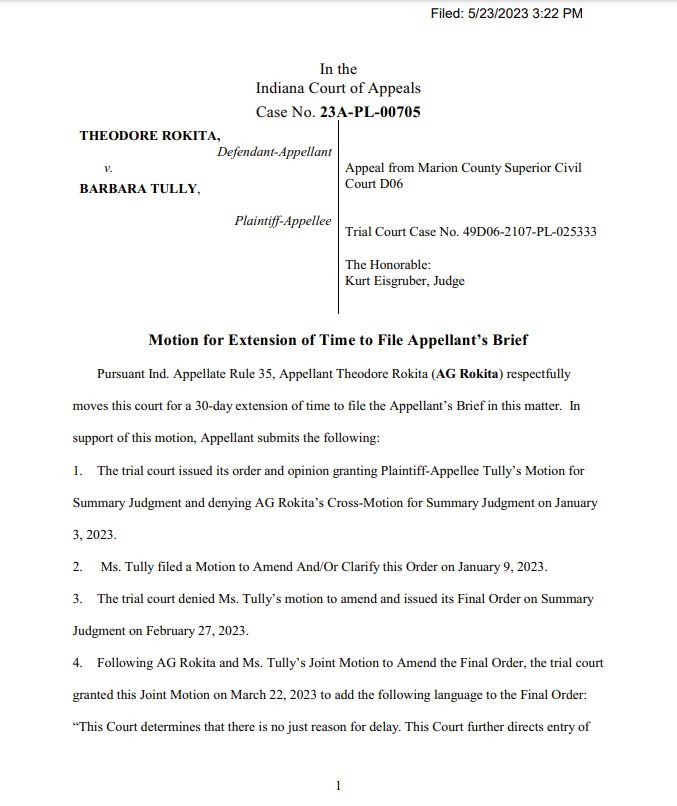

The Marion Superior Court has ordered Rokita to release the informal advisory opinion written by the Office of the Inspector General of Indiana. However, the attorney general’s office turned to the Court of Appeals of Indiana and hired James Bopp, a nationally known attorney advancing conservative issues, and his team to litigate the case.

Bopp’s motion for continuance has been granted, giving Rokita’s attorneys until July 19 to file their appeal brief with the appellate court.

Despite the trial court’s ruling in Tully v. Rokita, 23A-PL-00705, Bopp is optimistic the appellate court will find the inspector general’s informal advisory opinion is confidential. Rokita has argued that under state law, these kinds of opinions from the inspector general are not subject to public disclosure.

That stance got a boost during the waning hours of the 2023 Indiana legislative session when lawmakers inserted into the state’s biennial budget a provision. The amendment, crafted by the attorney general’s office, not only specifically stated informal advisory opinions are confidential but also made the protection retroactive to cover the opinion about Rokita issued in 2021.

“We will certainly be asserting that provision. It resolves the case,” Bopp said. “Of course, the attorney general has argued and we’ll continue to argue…even without that legislative enactment that existing law still provides for the confidentiality of these informal advisory opinions.”

However, before the Bopp attorneys can present their arguments to the Court of Appeals, they need the extension to tend to two cases in federal court.

One is a lawsuit challenging what Bopp’s client, Indiana Right to Life Victory Fund, claims is Indiana’s unconstitutional restriction on corporate contributions to super PACs. A slew of state officials, including Rokita, have been named as defendants in their official capacities.

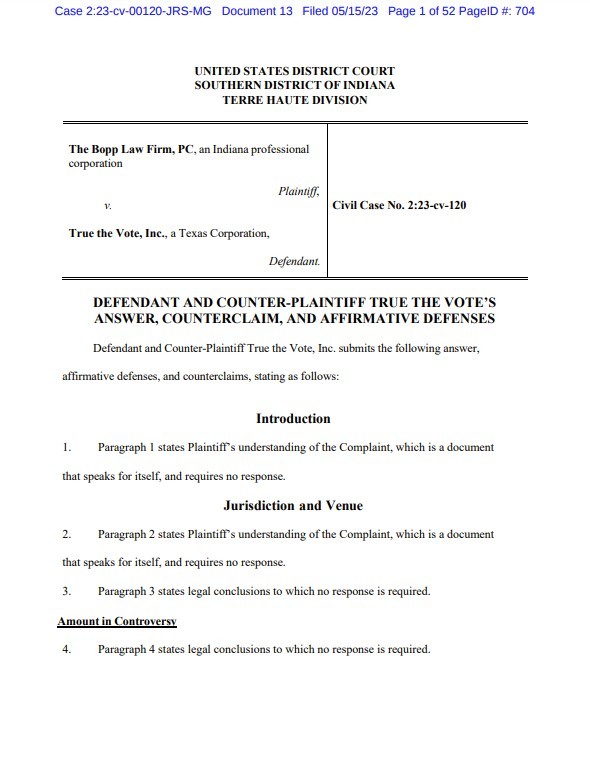

The other lawsuit is the Bopp firm’s own litigation asserting True the Vote, a Texas-based nonprofit, owes $1.06 million for legal services. True the Vote has hit back, filing a counterclaim that asserts the Bopp firm provided “substandard legal services” and made “fraudulent misrepresentations about their experience, skills and ability.”

Speaking to The Indiana Citizen, an indignant Bopp denied the accusations, calling them “outrageously disgustingly false.”

“What they do is they throw mud at you,” Bopp said. “They make scurrilous accusations. They try to attack your character and reputation because they want to keep the money for themselves.”

True the Vote’s attorney, Michael Wynne, co-chair of Gregor Wynne Arney in Houston, Texas, did not respond to a request for comment.

Conflict waiver

The attorney general’s office entered into a contract with The Bopp Law Firm in April to provide legal services in civil lawsuits, enforcement of administrative orders and civil appeals. Bopp’s fee was set at $200 per hour, with the total amount capped at $250,000.

As part of the contract, the attorney general included a conflict of interest waiver for the case, Indiana Right to Life Victory Fund, Sarkes Tarzian, Inc., v. Diego Morales, in his official capacity as Secretary of State, 22-1562. The defendants in the case are public officials who enforce the state’s political contributions laws including the secretary of state, the Marion and Monroe county prosecutors and the co-directors of the Indiana Election Division.

In addition to Rokita being named as a defendant, the attorney general’s office is representing all the defendants in this case.

Cari Lynn Sheehan, attorney and clinical assistant professor of business law and ethics at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business, said the question of whether the attorney general should have gotten written consent from all the other defendants before including the waiver in the contract was difficult to answer.

She was speaking about conflict of interest waivers in general and had not read the state’s contract with the Bopp firm. But she said, as a general matter, the other co-defendants would not need to give their consent for the waiver. Since Bopp is representing only Rokita in the lawsuit about the inspector general’s advisory opinion, the other officials on the defense side would not need to be notified.

“It’s specific to the one party,” Sheehan said. “You don’t have to get waivers from all co-defendants, in general, in a matter … and you don’t have to really disclose it to other co-defendants.”

The attorney general’s office did not respond to a question asking if it had gotten consent from all the defendants. Angela Nussmeyer, co-director of the Indiana Election Division, and the Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office said they had not been notified about the waiver. The Secretary of State’s office declined to talk about pending litigation. The other defendants contacted did not respond to inquiries from The Indiana Citizen.

Bopp said he got consent from Indiana Right to Life and the attorney general. Even so, he does not see a conflict because Tully and Indiana Right to Life Victory Fund are about very different legal issues and neither plaintiff is holding a position directly opposed to the other.

“There is nothing adverse,” Bopp said. “… So there is no conflict and even if there were, they were waived.”

A waiver of conflict, Sheehan said, requires consent from the clients at the start. The clients need to be told of the conflict and given some details related to the matter, like the identity of the potential new client and the nature of the legal work, in order to be able to make a “reasonable informed decision” about whether to give consent.

Not getting consent, Sheehan said, could make the attorney a target of litigation.

“If you don’t get the waiver, there’s a potential that you could be sued for malpractice,” Sheehan said. “You can get disqualified from the case, meaning the other side can seek to have you removed as the attorneys. So there are some big ramifications if you don’t comply.”

Election law question

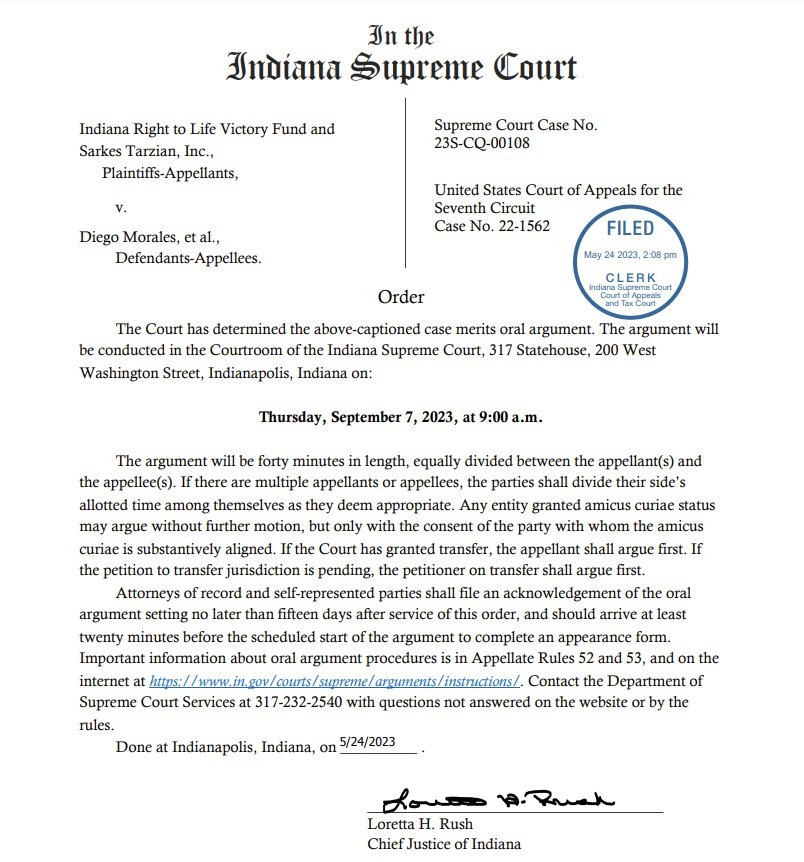

The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals recently pitched the Indiana Right to Life Victory Fund case to the Indiana Supreme Court. Before the appellate judges could determine if the Victory Fund has standing to file the lawsuit, they want to know what the state’s election code means.

According to court filings, the Victory Fund wants to operate as an “independent-expenditure PAC” or what is commonly known as a super PAC. It would not funnel donations directly to candidates but, rather, spend the money to advocate on particular issues or ballot initiatives.

Indiana election code limits corporate contributions to $5,000 per year to candidates for statewide elected office and bans corporations from using PACS to get around the contribution cap. However, the statute is silent about corporate contributions to a PAC for independent expenditures, placing neither a limit nor a restriction on monetary donations.

The lawsuit arises from the fear that Sarkes Tarzian, Inc., the co-plaintiff, will violate election contribution laws and face criminal penalties if it contributes $10,000 to the Victory Fund.

Consequently, the plaintiffs make a two-step legal argument. First, they assert that by not specifically authorizing independent expenditure contributions, Indiana prohibits such donations. Second, the inferred prohibition on corporations giving money to independent-expenditure PACs violates the Constitution’s protections on free speech. scheduled oral arguments

The attorney general’s office called the litigation a “manufactured lawsuit.” It argued the plaintiffs did not have standing to file the complaint in federal court because state officials had not threatened them with any kind of enforcement for exceeding a perceived limit on contributions to super PACs.

After the Southern Indiana District Court dismissed the case, the plaintiffs appealed and the 7th Circuit in April sent the question to the Indiana justices. The federal appellate court asked: “Does the Indiana Election Code – in particular (Indiana Code section) 3-9-32-3 to -6 – prohibit or otherwise limit corporate contributions to PACs or other entities that engage in independent campaign-related expenditures?”

The Supreme Court has scheduled oral arguments for Sept. 7 in Indiana Right to Life Victory Fund et al. v. Diego Morales, et al., 23S-CQ-00108.

Bopp said whatever Indiana’s highest court rules, his clients will win.

“If the law is interpreted as not prohibiting unlimited contributions from corporations to PACs for independent expenditures, we win. Now they can do it,” Bopp said. “If the Indiana Supreme Court interprets the law as prohibiting us, then we go back to the 7th Circuit on, ‘Is this constitutional?’ … There’s no question we win this under the Constitution.”

Overdue bill

As for the dispute over legal fees, Bopp said he has notified True the Vote and its lawyer team that if they don’t withdraw their counterclaims, he will seek monetary sanctions against both the nonprofit and its legal counsel. The Terre Haute attorney is preparing to file a complaint under Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which allows clients and lawyers to be penalized for bringing baseless claims.

The case is the Bopp Law Firm, PC v. True the Vote, Inc., 2:23-cv-120, and is filed in the Southern Indiana District Court.

In his 50-year career, Bopp said he has never used Rule 11 to recoup legal fees. “But, I’ve never seen such an outrageous set of totally unfounded allegations. They are just trying to smear me and avoid payment of a debt so they can pay themselves.”

Bopp’s complaint for unpaid legal fees coincides with allegations of financial impropriety lodged against True the Vote. ProPublica has reported the Campaign for Accountability filed a complaint with the Internal Revenue Service alleging founder Catherine Engelbrecht and co-founder director Gregg Phillips “used the nonprofit True the Vote to enrich themselves.”

In its counterclaim, True the Vote asserted multiple issues with the Bopp firm’s handling of cases and billing practices.

The nonprofit alleged the Bopp firm was given a $1.1 million retainer for an array of legal work including filing a “series of cases in federal courts in various states.” A week after filing cases in the four states of Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which cost $280,960.90 in filing fees, the Bopp firm recommended the claim be voluntarily dismissed. The filing fees were not reimbursed.

In addition, Truth the Vote claimed the Bopp firm failed to provide “clear invoicing product or work product.” An audit by the nonprofit’s bookkeepers, certified public accountants and two outside law firms “could not understand the BLF invoices or trust account fund summaries.”

Subsequently, the Bopp firm submitted an invoice for $10,393 for time spent resending and explaining previously drafted invoices in response to the audit, according to the counterclaim.

The counterclaim caught Bopp by surprise. His legal work for True the Vote dates back to his representing the nonprofit’s predecessor, King Street Patriots, in a case that went before the Texas Supreme Court and has continued to where he considered Engelbrecht, the group’s co-founder, a friend.

He claimed he won all four cases in which True the Vote was a defendant.

“Up until the parting of the ways, they did nothing but praise my work and urge me to continue to represent them,” Bopp said, “and were giving me projects … to look into, to research on whether or not they would have me bring further suits.”